The Story of the Wittenberg Concord – Kittelson on Luther

I mentioned previously that I had read this book and found some of its material interesting enough to share with you, gentle readers.

This piece is Kittelson’s description of how the Wittenberg Concord, as they say, went down. I found it to be a rather interesting story, and one that I had not heard before in anything like this much detail. So bear with me as this is going to be long. But you just might learn something like I did. The setting is Spring 1536.

James M. Kittelson, Luther the Reformer: The Story of the Man and His Career (Fortress, 2003), 267–68.

==================================

Follow @WTravisMcMaken

This piece is Kittelson’s description of how the Wittenberg Concord, as they say, went down. I found it to be a rather interesting story, and one that I had not heard before in anything like this much detail. So bear with me as this is going to be long. But you just might learn something like I did. The setting is Spring 1536.

James M. Kittelson, Luther the Reformer: The Story of the Man and His Career (Fortress, 2003), 267–68.

|

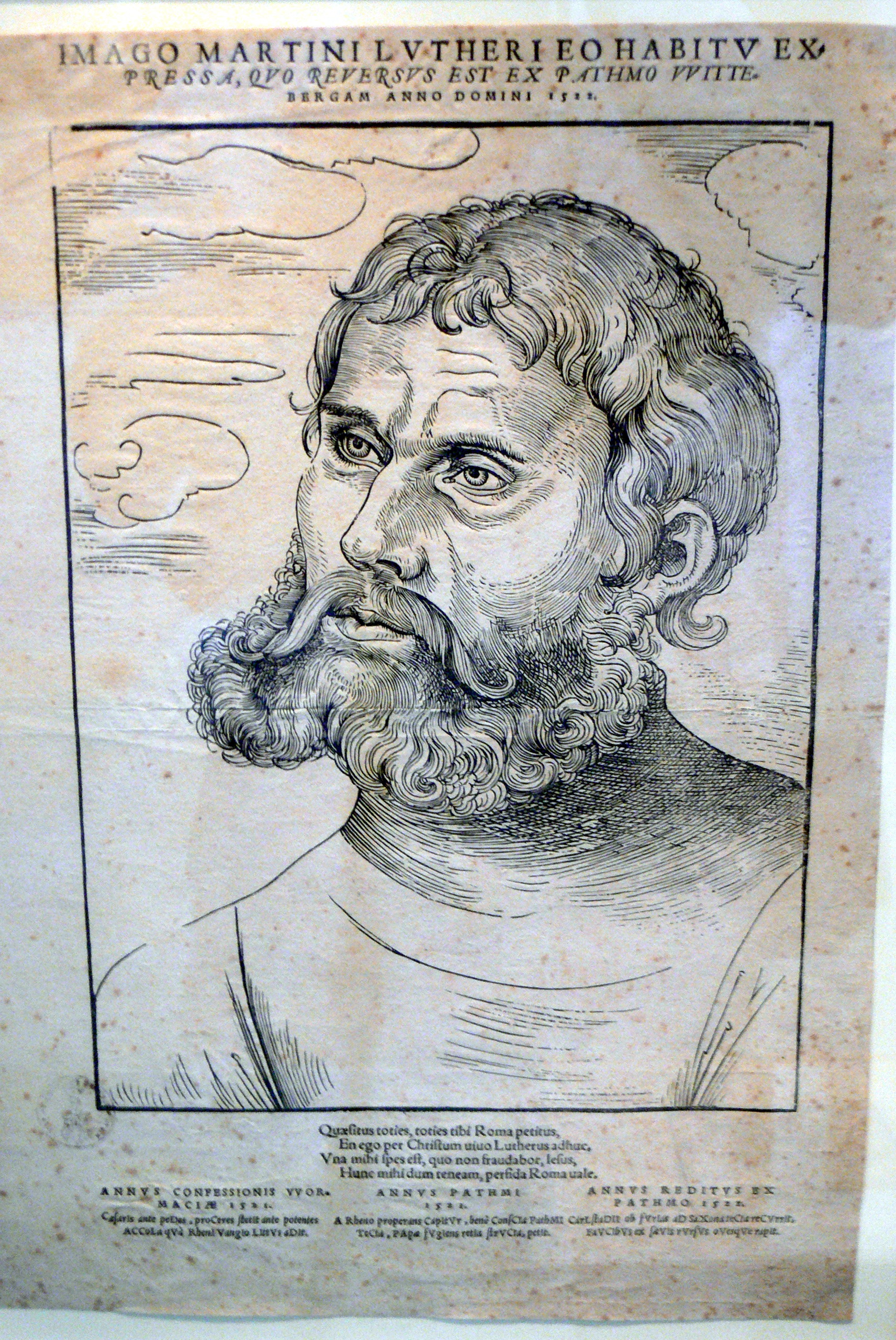

| Lucas Cranach the Elder [CC BY-SA 4.0-3.0-2.5-2.0-1.0], via Wikimedia Commons |

Unpredictably, Luther also showed himself willing to overlook, at least for the moment, one misstep on the part of the Strasbourg pastors. In February Bucer and Capito participated in writing a confession for the Baslers in which they minimized the physical presence of Christ in the bread and the wine. Perhaps unaware of what had transpired, Luther still invited them and other south German theologians to a meeting at Eisenach on May 14. There they could discuss whatever differences remained.

In the interim, Luther’s suspicions had returned. When the southerners arrived at Eisenach, there was no Luther. Days passed, and he had still not arrived. They traveled further east and there received a message from Luther in which the reformer pleaded yet another outbreak of illness and asked them to meet him not far beyond Leipzig. Bucer preempted these delays. He replied that the entire party would come to Wittenberg.

When they arrived, they learned that for unexplained reasons Luther would not meet with them. But then early the next morning they were suddenly called into his presence. Equally suddenly, the meeting was adjourned until mid-afternoon. Finally Bucer had a chance to explain at length all he had done in the last years for the sake of concord. Luther still appeared to be filled with suspicion. He replied by declaring that Bucer and Capito had to condemn Zwingli’s teachings explicitly and declare their belief in the real presence without regard to the communicants’ faith or lack of faith. After listening to a few words in response, Luther said that he felt faint and had to leave so that he could rest.

Skilled debater that he was, Luther had exposed the sorest point between them. With great care, Bucer and Capito had covered over the issue of what a person without faith received in the Lord’s Supper. Did the real presence of Christ’s body and blood depend on the communicant’s disposition? To an unbeliever, were the elements merely bread and wine? How was Paul’s declaration that whoever ate and drank in an “unworthy manner” brought “judgment on himself” to be understood? True to his reading of the gospel, Luther held that one who believed the words of Christ’s institution was a Christian. In this passage, therefore, the unfaithful and the unworthy were identical, and they received Christ’s body and blood, although they did so to their judgment. By the same token, for Bucer and Capito it remained unthinkable that bread and wine could—in and of themselves, with only the Words of Institution and without faith—be the body and blood of Christ.

Luther’s last demand crushed the delegation from south Germany. They could freedly deny that they had ever taught as Zwingli had done, or at least like the Zwingli of the Ratio Fidei that had been circulated at the Diet of Augsburg. But granting that infidels could eat the body of Christ with their teeth and drink his blood with their tongues was another matter. What the south Germans did not know was that Luther himself was unable to sleep that night.

The next afternoon, Bucer replied. He and his colleagues had never taught that the bread and the wine were mere symbols of Christ’s body and blood. To the extent that Zwingli had done so, he was in error. As to the second demand, Bucer declared that all who came to the Lord’s Supper were among the unworthy, and that all (even those without a living faith) were offered the body and blood of Christ in the Supper.

Luther asked if each of the south Germans was in agreement with Bucer’s confession. When they said they were, he turned to his colleagues from Wittenberg and asked if they were satisfied. They talked a little, but nodded their agreement. Luther asked Bucer, Capito, and the others once again if they truly believed what Bucer had said. They said they did. Abruptly, Luther radiated joy and kindness. He declared that they were all in concord and brothers in Christ.

Bucer and Capito wept. Luther had gone an uncharacteristic extra step. He had passed over the question of what the unworthy received in the Lord’s Supper and the problem of the precise relationship between “faith” and “worthiness.” For the sake of unity, he had contented himself with what Bucer offered.

==================================

Follow @WTravisMcMaken

Comments