The Praxis of Empathy - Michael Jimenez on Theology as Biography

|

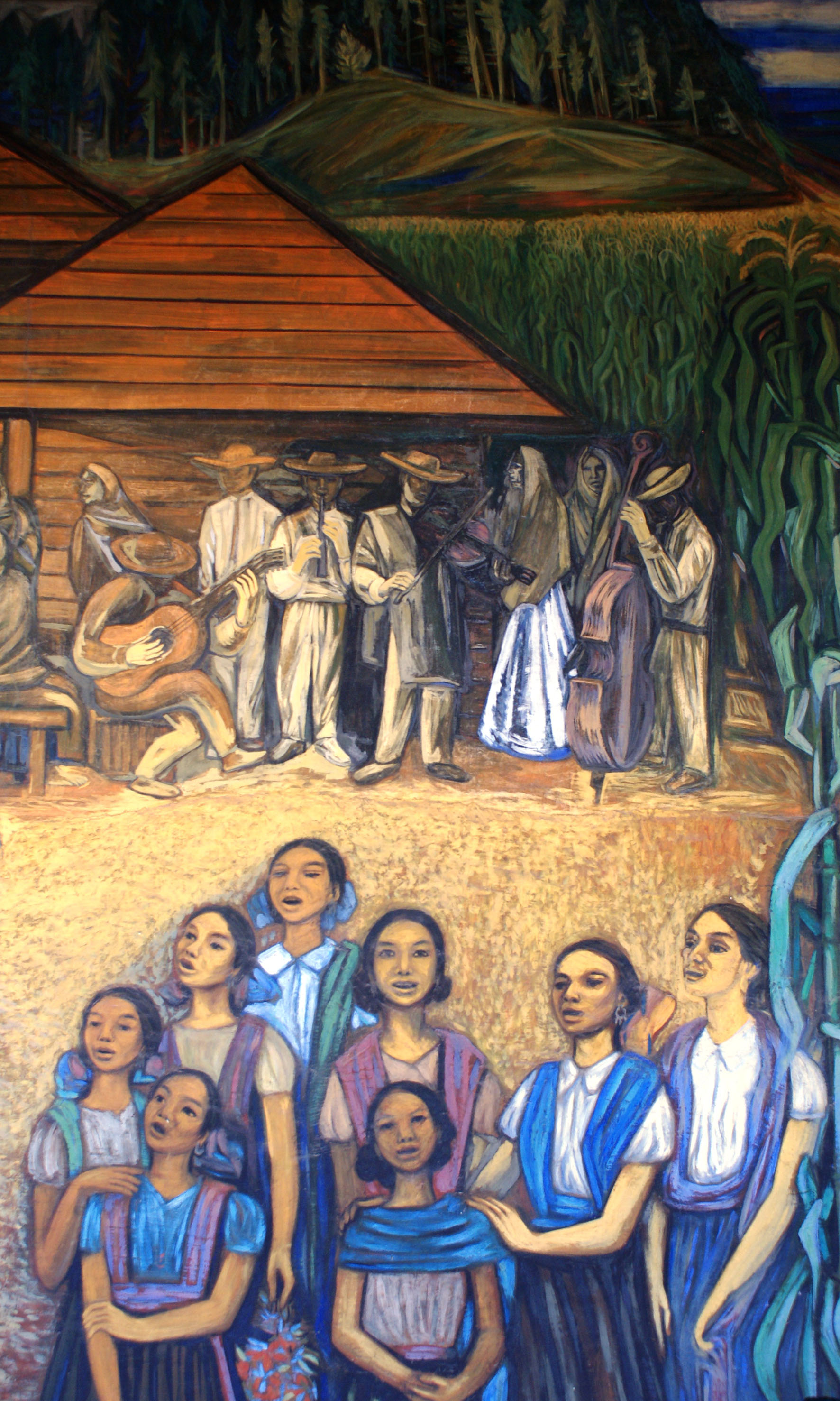

| Fragmento de pintura mural, By VeoKenxiz (Fotografía propia) CC BY-SA 3.0 (https://creativecommons.org/licenses/by-sa/3.0)] via Wikimedia Commons |

Remembering Lived Lives: A Historiography from the Underside of Modernity, Michael Jimenez (Eugene, OR: Cascade Books, 2017).

Along the way, Jimenez draws upon seemingly surprising interlocutors -- namely, the white Protestant theologians Karl Barth and James McClendon. From Barth's Ethics of Creation he retrieves the notion of a moral hermeneutic embracing the "far neighbor." Jimenez plays off this notion against Barth's own limitations as a Eurocentric thinker and icon of the Western theological canon. From McClendon Jimenez appropriates the notion that good theology is biography; encountering the lived experience of others, often across vast social and cultural differences, dissolves narrow preconceptions and can breathe new life into old questions. This program, as I read it, is not some some gesture toward a politically correct ideal of multiculturalism; rather, Jimenez is arguing that writers from the third world are making original contributions in literature and theory in their own right that more of us -- that all of us -- should be taking seriously.

Cultivating historical awareness can be a dangerous project, especially when it comes to facing our collective complicity in the oppression of and violence against marginalized groups, as theologian Johann Baptist Metz recognized. The demands of professional specialization notwithstanding, Jimenez suggests that theologians and other scholars might be leery of serious historical study for more existential reasons -- namely, it challenges our own tribal certainties. Jimenez writes:

Historical consciousness disrupts narratives of exceptionalism and purity about religion, God, and the nation-state. For some it is better to live with amnesia than have their myths annihilated. One of my goals is to awaken the reader out of their ahistorical dogmatic slumbers (p. 4)

One model for using the life stories of historical figures that Jimenez commends as a source of insight is James H. Cone’s comparison of Martin Luther King Jr. and Malcolm X; the laudable notion here is that wrestling with the life and work of these great African American thinkers, whose differences are seen as complementary, will challenge, enrich, and broaden the practice of the theology as a whole. The same is true, Jimenez argues, with the biographies and writings of the Jesuit Ignacio Ellacuria and the other martyrs of El Salvador.

Not only biography but also fiction can be a vehicle for conveying and exploring difficult historical truths. In that vein, Jimenez, in a chapter on history and the cinema, offers an insightful interpretation of Roland Joffé's brilliant film The Mission, which dramatizes the struggle of European Jesuits in the 1740s to save a Guarani mission community in a Paraguayan region being transferred from Spanish to Portuguese colonial rule. The film brilliantly explores, without resolving, religious and ethical questions of justice and violence in service of defending the oppressed. Jimenez does not shy away, though, from the ambiguities of the film, from a postcolonial perspective -- for example, its depictions of the indigenous Americans -- and especially the women among them -- in romanticized and largely passive roles.

Even with its focus on methodology, this is still a very personal book, rehearsing the author's own voyage of discovery. Jimenez recounts how he -- an hispanic American from California who was educated in evangelical Protestant institutions and began learning Spanish at a fairly late age -- gradually grew into his own mestizo consciousness, largely prompted by academic study. His evident excitement for this project gives the book a somewhat frenetic and unfinished quality. Some provocative suggestions could use a bit more development; specifically, I'd like to read him engaging in more concrete examples of the revisionist storytelling he comments (though I realize that might be a tall order in a book largely on method). I hope he pursues some of these threads in his ongoing work. For my part, reading this book has helped goad me to plunge into some less familiar sections of the library bookshelves.

==================================

Follow @jsjackson15

Comments