§1 Approaching Galatians (session 4, part 1)—Paul’s Letter to the Galatians: A Presbyterian Adult Spiritual Formation Series

[The

series continues and now commences the fourth in-person session. Find the last post here.]

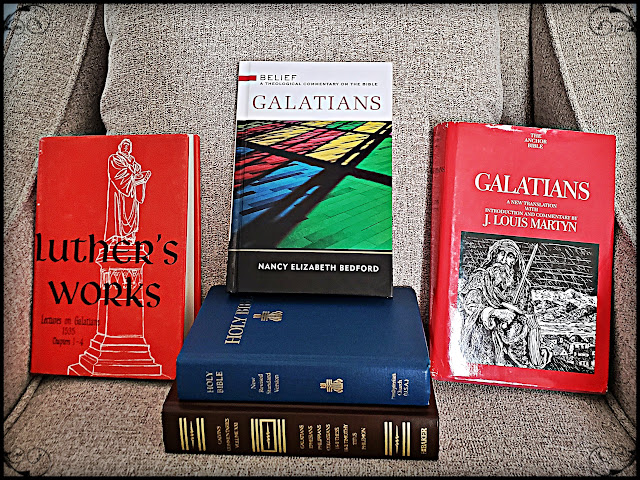

McMaken: Welcome, faithful remnant of our study together. We are fewer today—thanks to all the ice, I'm sure. I’d like to begin with a quick recap. We’ve talked about the date of the writing and the audience to whom Paul was writing. We also worked our way through some key sources that I'm using to fuel reflection. We talked about Luther: his two kinds of righteousness, his two kingdoms, his two uses of the law, and his ideas about justification by faith. We talked about Calvin: his work on his biblical commentaries and how he has similar but different focuses from Luther. Then, last time, we talked about J. Louis Martyn—who has done a lot of work on reading Paul through an apocalyptic lens—as well as some of the history of scholarship around research into Jesus and Paul. Today, we have one last book to talk about before we get into the text!

e.

Nancy Bedford and Galatians

This last book is Nancy Bedford’s

book on Galatians in the Belief: A Theological

Commentary on the Bible series.[1]

If you want to read one of the books that I’m using in this series, then this

is the one you should pick up. It's written for as broad an audience as

possible, so it is more accessible than some of the others. Bedford also has

some interesting scholarly contributions, including how she thinks about the

outline of the book of Galatians, which we'll get to in a bit. Her approach is

to think broadly about how the different Christian traditions of interpreting

Galatians fit together and what it can mean for us today, including some of

those more practical applications for us in our lives.

How does

Bedford understand the Galatians, the recipients of this letter? She speaks

about the letter in terms of intra-Christian debates. Paul is arguing with his

opponents, and the Galatians are stuck in the middle. It isn’t a situation of

Christians on one side and Jews on the other—everyone involved in the argument

is a “Christian.” We've been over this idea a few times already. Bedford

basically agrees, although she speaks in terms of “intra-Christian” debate.

Strictly speaking, that suggests a highly developed concept and identity of

“Christian” in distinction from the Jewish community that wasn’t around in

Paul’s day. It’s later language pushed back in time, as it were. But Bedford is

getting at the right idea. If we wanted to be more technical, as we’ve done

before, we’d say that we're talking about some Jewish-Jesus followers arguing

with other Jewish-Jesus followers about what to do with Gentile-Jesus

followers.

Bedford

thinks that these intra-Christian debates, these debates among different groups

of Jesus-followers, are serious debates. They are more serious, for example,

than Calvin's way of framing it about differences in customs between churches,

where one church expects another church to do things the same way they do them.

The question at stake is: How are Jewish Jesus-followers going to incorporate

Gentile Jesus-followers into the Jesus-following community?

This wasn’t

a totally new or surprising question at the time Paul wrote Galatians. The

question has new inflections because it’s all now centered on Jesus, but the

Jewish community had been interacting with Gentiles, and with Gentiles who were

interested in the whole Jewish religious thing, for quite a while. Versions of

this question are all through the Hebrew scriptures. Even more recently, there

was Jewish contact with what we called Hellenism—the cultural environment that

comes out of Greece and the Greek colonies and cities all around the Eastern

Mediterranean. Alexander the Great’s empire in the 4th century BCE was a large

part of the story of Greek culture expanding throughout the Eastern

Mediterranean, including Palestine. When he died, his kingdom splintered into

different pieces. He was Greek, so you've got Greek control of all these

different sections of his empire. One piece of that previous empire was run out

of Syria and included Palestine.

Fast forward

a few centuries and you get to a king named Antiochus the 4th Epiphanes. An “epiphany”

is like a revelation, an experience of God, a knowing of God. Basically,

Antiochus thought he was literally God's gift—well, not “God’s” gift; more like

“a god’s” gift, but you get the idea. Antiochus was all about the superiority

of Greek culture, and he tried to impose this throughout his kingdom in a new

way. Suddenly, you've got the situation in Jerusalem where Antiochus expects

the Jewish temple not to be devoted only to the one Jewish God, but to be

devoted to all the Greek gods as well. And in some ways, Antiochus wanted to be

treated like a god as well. The way this played out in Jewish areas was predictable.

It wasn't a very popular move, although many—or, at least, some—of the more

urban and well-off Jewish folks seem to have been on board and wanted access to

the benefits of Hellenization. But then Antiochus and his soldiers barged their

way into the temple and sacrificed the pig in the inner precincts. This added

insult to injury, as it were, because the Jewish tradition regards pigs as

unclean animals. It was at that point that a minor house in the priestly

lineage in Judea arose. They were called the Maccabees. Scholars aren’t

entirely sure what “Maccabees” means but the best guess is that it means “hammer.”

So Judah Maccabee, Judah the Hammer, raises an army in rebellion. Have we all seen

the movie Braveheart? That how I always picture what’s goeing on here.

They're out in the hills among the shepherds, putting together a ragtag army,

until – eventually – the meet Antiochus' forces in a pitched battle.

Surprisingly, Antiochus loses, and the Maccabees end up establishing their own

rule. That lasted from about 160 BCE to 63 BCE, when Rome marched in and took

over.

All through

this period, however, there are intense debates about how much Greek-ness, or

Hellenism, Jews are willing to tolerate. With the Maccabees in control in

Palestine, things tend to be more conservative with less Hellenization. But out

in the diaspora, among the Jewish communities outside of Palestine, things look

different. The diaspora is made up of Jews who left Palestine for one reason or

another, whether voluntarily or through forced emigration, throughout the first

millennium BCE. There are Jewish communities in many Greek cities throughout

the eastern Mediterranean, for instance. There are also significant Jewish

communities in Babylon and Egypt. They had synagogues where they gathered,

prayed, and read their Scriptures, whether in Hebrew or in Greek translation. And

in the Greek-speaking diaspora, there was not sharp conflict between Jewish and

Greek culture.

From the Hellenistic

perspective, there are lots of gods and lots of different people worshiping

them, so what’s the problem with one more? Additionally, Hellenistic culture

had a high regard for things that were old and, of course, the Jewish people

and their beliefs are very old. Hellenistic folks saw a venerable old tradition

maintained by a particular group of people who weren’t harming anyone. They

figure that just means there’s one more god invested in the success and safety

of their city, which is a good thing. And there was a lot of fluidity between

Jewish communities in these cities and the Hellenistic communities on the side

of Jews in diaspora, even to the point where there seems to be attestation in

the records of Jewish folks being involved in all kinds of different civic

organizations. Think if groups like the Knights of Columbus, the Masons, or the

Better Business Bureau—but with different rituals and observances tied to pagan

gods. These organizations help make the community function well by making sure

that the city’s gods help it to prosper. People who disrupt that function are

bad. But Jewish folks were able to fit into this social situation without

causing any of those kinds of problems because they didn’t seem to think it

somehow compromised their devotion to the Lord.

Part of the

conceptual world that helped make sense of all this religious intermingling is

monotheism. The idea of monotheism, that only one God exists, wasn’t common in

the ancient world. Each group of people thought their god was the best god and

the high god, but everybody accepted that all the gods existed. So, for Jewish

folks, the other gods ultimately answered to their God, but that doesn't mean

they don't exist. The world is full of these kinds of spiritual powers and

forces, like we talked about with apocalyptic thought. From the perspective of

diaspora Jewish, what’s the problem with being associated with other gods that

exist so long as their ultimate allegiance is to the Lord, whom they believe is

the high god? Nothing. Given this kind of perspective, Jewish folks in these

communities could be good citizens right along with the Hellenistic folks.

So,

there’s a long tradition and broad spectrum of how Jewish folks in different

contexts think about their interactions with Gentiles and Greek culture. In Palestine—in

the Promised Land, so to speak—these boundaries are much more strictly

maintained than in the diaspora, where the boundaries are very fluid. One

question that then arises for the Jewish communities is: what do you do with

Gentiles who become interested in and devoted to the Jewish God, the Lord?

Ultimately, there are two levels of interest or involvement here, and reference

to both comes up from time to time in the New Testament.

“God-fearers”

are the first category. These are Gentiles who became impressed with the Jewish

god and added that god to the other gods that they worshiped. Many folks in the

ancient world thought that you can never have too many gods on your side. So

these Gentiles spent time with the Jewish communities gathered around the

synagogues, listened to the scriptures read and prayers said, and generally

learned about what devotion to the Lord means. But all the while they are still

worshiping their families’ and cities’ gods.

The second

category of Gentiles interested in the Jewish god is “proselytes.” Proselytes

are full-blown converts who leave their other family ties and the gods that go

with them and become, for all practical purposes, Jewish. The main way that

they do this is through circumcision, which is why circumcision shows up in

Galatians and becomes such a big deal in Paul's letters. The idea here is that

someone who was a Gentile now becomes a Jew, and therefore is no longer a

Gentile. And this involved changing your allegiance to deities. Now, as far as

we can tell, this was a rare occurrence because it meant such a dramatic change

in one’s life: completely new religious and ethical commitments, completely new

social locations, the loss of family ties, etc. God-fearers were more common,

but proselytes were rare.

Participant: Does this mean that only men are Jews? How did Women

become Jews?

McMaken: Your husband. That's really your only option. Or you could

marry a Jewish man, but your Gentile family probably wouldn’t allow that. Women

didn’t have much, if any, say over who they married. But, if you’re a woman who

was a Gentile and is now a Jew, either that’s because your husband converted or

you married in.

Participant: I would imagine they're not thinking about this as

individualistically as we do. There's an individual element to salvation. But

if you convert from Judaism to Christianity, you're probably doing so as a

household. Not necessarily just this one person.

McMaken: It would depend on your status in the family. If the paterfamilias

changed, then everybody changes. But if you’re the second son, for instance, you're

probably not taking many people with you.

Now, here is

something that is really interesting. There seems to have been a minority

position within the Jewish conversation at the time that said it was impossible

for Gentiles to become Jews, even if they do the whole proselyte thing. Paula

Fredricksen, whom I’ve talked about before, thinks that Paul might have been

part of this group.[2] I

think that makes a lot of sense, and we’ll come back to that topic as we go

along.

So, if that’s

how Gentiles could become part of the Jewish community apart from any consideration

of Jesus, then what happens when you add Jesus to this dynamic? Well, on the

one hand, you have the people Paul is arguing with in Galatians who seem to

think that if Gentiles want to participate in the Jesus thing, then they need to

take the steps that Gentile proselytes take to become Jews—they need to be

circumcised. And since they are becoming Jewish through circumcision, they also

need to observe the Jewish law and keep what we would today call a kosher diet.

Folks who answered the question this way drew on a pattern that was already in

place, especially outside of Palestine in the diaspora Jewish communities

around the Roman Empire.

But Paul has

a very different idea of how this should go. He argues that Gentiles don't have

to become Jewish proselytes in order to follow Jesus. He thinks that there is a

Gentile way of following Jesus that does not require them to become Jews. Fredriksen

talks about “eschatological Gentiles”[3]

because, as part of that apocalyptic expectation, as part of the Jewish

traditions of thinking about what's going to happen when God makes everything

right, there is this idea that Gentiles are going to be included in what God

does. You see this especially in Isaiah, which Paul draws on through the Book

of Romans when he's thinking about these things. This is Isaiah 2:1–5:[4]

The word

that Isaiah son of Amoz saw concerning Judah and Jerusalem.

2 In days to

come

the mountain of the Lord’s house

shall be

established as the highest of the mountains

and shall be raised above the hills;

Have you ever read in the Psalms and

noticed a heading on one of them calling it a Psalm of Ascent? That means it is

a Psalm of “going up.” They have this name because in the Jewish mind, both

geographically and in terms of elevation, you always went “up” to Jerusalem. Jerusalem

and the temple are up on the top of a hill, so when you go there, you have to

go “up” the hill. And this takes on symbolic meaning as well with the idea that

the temple is where God lives, and it is the high, central point where heaven

and earth touch. So you always go “up,” an this passage in Isaiah predicts a

time when—literally, or at least symbolically—this becomes true for the whole

world and not just for Jews. The passage continues:

all the

nations shall stream to it.

“Nations” here refers to the folks

we’ve been calling “Gentiles.” So the Gentiles are streaming to the Lord’s

house.

3 Many peoples shall come and say,

“Come, let

us go up to the mountain of the Lord,

to the house of the God of Jacob,

that he may

teach us his ways

and that we may walk in his paths.”

When we read this passage from our

contemporary Christian perspective, we make a mental substitution in our mind

so that we take “many peoples” to mean “many people.” We assume that this means

a large group of individuals, a large group of people. But what the text is

really talking about is all the many “nations” that we just read about. These

are all the different kinds of Gentiles that exist in the world, and they are

all streaming to the Lord’s house.

For out of

Zion shall go forth instruction

and the word of the Lord from Jerusalem.

4 He shall

judge between the nations

and shall arbitrate for many peoples;

they shall

beat their swords into plowshares

and their spears into pruning hooks;

nation shall

not lift up sword against nation;

neither shall they learn war any more.

5 O house of

Jacob,

come, let us walk

in the light

of the Lord!

So, as reflected in and developing

from this passage in Isaiah, there was this expectation that when God shows up

to set the world right in the end, all the Gentiles are going to get really interested

in Israel's God. And, in this passage: do the Gentile nations ever stop being

the nations? Does it say they're going to come and become Jews? No. The nations

stay the nations. Sure, they stop fighting each other. They stop engaging in

typical Gentile behavior. But they are still Gentiles. All the Gentiles are

coming to Zion, to Jerusalem, and God is judging among the Gentiles—basically,

what we see here is the idea that the sovereignty of Israel’s God over all

things will be real and effectual in a new kind of way. It is what you might

expect if you prayed for God’s kingdom to come and God’s will to be done, and

then it very straightforwardly was! But all of these different kinds of Gentiles,

these nations, are listening, learning, and obeying the God of Israel while

remaining Gentiles.

This seems

to be the way of thinking that Paul works within and adapts to the new

situation, the new time on God’s clock, that he sees as the result of Jesus. Paul

sees Gentiles getting in on the Jesus thing and thinks of them in terms of

these “eschatological gentiles” (to circle back to Fredriksen).[5]

And, just like the nations in Isaiah 2, Paul doesn’t think that the Gentiles have

to stop being Gentiles in order to worship and obey the Lord. Thanks to Jesus,

thse Gentiles are now involved with God, they are part of God’s work in the

world, and they are part of a people of God that still has Israel at its core

but has now expanded beyond Israel to the nations.

Importantly,

for Paul, if you make these Gentiles become Jews then you’re getting in the way

of what God is doing in this new “age,” this new time on God’s clock. If you

make Gentiles become Jews, then they can’t be these eschatological Gentiles.

For Paul and this tradition he follows—which, again, seems to have been a

minority report in his day—Israel is supposed to say Israel, the Gentiles are

supposed to stay Gentiles, and the Lord is Lord over all of them. And that’s

why it would make sense if Paul didn’t think a Gentile could really become a

Jew through conversion as a proselyte. Why? Because, building on this sort of

tradition we see in Isaiah, the Gentiles aren't supposed to become Jews: they

are supposed to become eschatological Gentiles.

It is

important to understand this to understand all the negative comments Paul makes

about circumcision in his letters. Whenever he does that, whether in Galatians

5 when he wishes his opponents might castrate themselves, or in Phillians 2 when

he talks about the “dogs…who mutilate the flesh”[6]—Paul

is not talking about Jewish people who are circumcising their sons on the eighth

day. He's talking about those giving and receiving proselyte circumcision and

he’s denigrating the fact that they think they can turn Gentiles into Jews by

circumcising them. That's what he rejects and that’s what he’s criticizing. His

criticism of proselyte circumcision and of following the Jewish dietary guidelines

is not a rejection of Judaism or Jewish ways of following Jesus. Paul’s point

is that these things don’t apply to Gentiles because Gentiles, based on this

tradition out of Isaiah, don't need to become Jews in the last days. God will deal

with them precisely as eschatological Gentiles. To come back to Bedford, she

has a nice turn of phrase that sums this up: “In Christ, there is ample room

for difference.”[7]

[This is an edited transcript from an adult spiritual formation group that met at St. Charles Presbyterian Church in St. Charles, Missouri. It was transcribed and edited with the help of a student worker at Lindenwood University who wishes to remain anonymous, but who was also a big help. Click here to find an index of the full series.]

==================================

Follow @WTravisMcMaken

Comments