Helmut Gollwitzer and John Webster on Scripture, or, the problem of *ethical* biblical criticism – A guest post by Collin Cornell

[Ed. note: Collin Cornell writes the always interesting blog Kaleidobible, as well as semi-regular guest posts here at DET.]

John Webster’s Holy Scripture: A Dogmatic Sketch (Cambridge, 2003) is a carefully argued fugue on one theme: reintegrating the doctrine of Scripture into a properly theological account of God’s saving work. Webster moves Scripture from its station as theological doorman and gives it place with the other main dogmatic foci. Like them, its adequacy depends on God’s act in Christ and not on standards drawn from elsewhere.

John Webster’s Holy Scripture: A Dogmatic Sketch (Cambridge, 2003) is a carefully argued fugue on one theme: reintegrating the doctrine of Scripture into a properly theological account of God’s saving work. Webster moves Scripture from its station as theological doorman and gives it place with the other main dogmatic foci. Like them, its adequacy depends on God’s act in Christ and not on standards drawn from elsewhere.

This also means that, rather delegating exegesis to general hermeneutics, Webster fleshes it afresh along more specifically Christian lines. As such, Webster extends the deeply Reformed tradition of suspicion towards the idolatrous self. “Reading Scripture is an episode in the history of sin and its overcoming; and overcoming sin is the sole work of Christ and the Spirit. The once-for-all abolition and the constant checking of our perverse desire to hold the text in thrall…can only be achieved through an act which is not our own” (89). Critical methods, then, represent for Webster “a false stance towards Scripture,” characterized not by child-like “teachableness” but by “mastery” (102).

This rings true to me. And yet I am also left wondering where this classical tradition of suspicion towards self and the modern legacy of suspicion towards Scripture intersect. Webster acknowledges the “creatureliness of the text” – mildly endorsing modern insights into the Bible’s complex development and gradient historicity (20). But it is hard to imagine what role various forms of ethical criticism could play in his proposal. How might one assume a childlike posture towards the Bible while also recognizing its pervasive patriarchy or class interests?

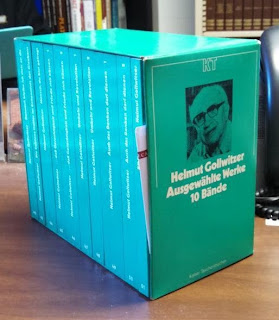

If Webster would give me no answer, perhaps others who shared his dialectical coordinates might. I turned to the chapter on the Bible in Helmut Gollwitzer’s Introduction to Protestant Theology (trans. David Cairns; Westminster John Knox, 1982). Gollwitzer’s (far shorter) presentation on the doctrine of Scripture addresses two problems: first, of biblical authority per se, and second, of the Bible’s material adequacy to function as authoritative.

Gollwitzer asks in the first instance whether claiming biblical authority effectively places some people (the biblical authors) in power over others (the churches). Is kyriarchy ingredient in biblical authority? The concern does not emerge from a secular egalitarianism; one of Gollwitzer’s fundamental convictions is that the gospel means freedom – spiritual and this-worldly. Can the Bible truly promote human emancipation if its adherents insist that its particular collection of human voices function as an unsurpassable court of theological appeal?

Gollwitzer postpones this question to ask a second: even if biblical authority per se is acceptable, is the Bible capable in the modern period of fulfilling its role as theological arbiter? Here Gollwitzer rehearses the familiar difficulties generated by biblical criticism, namely, the Bible’s gradient historicity and theological plurality.

Gollwitzer responds to these two questions by developing the interlocking concepts of faith and of witness. Faith in the biblical sense is “personal trust in God” (50). It cannot depend on the prior fulfillment of certain conditions, “namely, the act of submission to a human authority, either that of the church’s teaching office (the pope) or that of the biblical authors” (ibid). No human power must be confused with God’s word in which Christians put their personal trust. “By such investing of the Bible with divine authority, by laying down the previous condition of a work to be performed by us…as coming before trust in God’s word addressed to us, we involve ourselves in a hopeless contradiction with what the bible itself has to tell us about the nature of faith” (ibid.).

Rather, the Bible is a witness. Gollwitzer explains the Bible’s similarities in this regard to the church. The church, too, is deeply fallible, theologically disunited, and inevitably local in its history, point of view, and form (56). Yet God uses the church effectively to bring people to faith in Christ. And the church is united by its shared referentiality: in fact, its only unity may exist at the level of its common gaze upon Christ. So, too, is the Bible fallible, disunited, and local; its unity, too, is not formal but referential, pointing to Christ. Two features distinguish it from the church: its uniquely intensive authenticity to its message and its historical proximity to the events of God’s revelation. As a matter of experience over time, the church has found that these writings “thrust themselves” on the community, i.e., their trueness to God is self-attesting (54). The (relative) nearness of their writers to God’s acts of self-revelation in Israel and in Christ also sets them apart from other, subsequent ecclesial forms of testimony.

Gollwitzer’s deployment of these concepts, faith and witness, establish a strong differentiation between the Bible and the word of God, first from the human perspective and then from the divine. Christians trust God (and not, ultimately, the Bible); and God speaks (not, ultimately, the Bible). This distinction enables Gollwitzer to countenance a greater suspicion towards the Bible than Webster’s language about “creatureliness” allows. He goes so far as to encourage exegetes to point out “accommodations [in the biblical texts] to class interests” (60). Gollwitzer thus speaks not only of the Bible’s fallibility in matters of historiography, but also in ethics. Presumably this willingness to identify the interference of class interests could extend to include other forms of ethical criticism, e.g., feminist.

Most likely Webster would find that Gollwitzer’s use of “witness” as an organizing concept falls prey to “a curious textual equivalent of adoptionism,” i.e., it makes the relation between text and revelation too occasional, even arbitrary (24; one wonders if the fallibility of the scriptural witness is a purely formal acknowledgement on Webster’s telling, and authorizes no concrete examples). More important, perhaps, is the possibility that Gollwitzer’s project betrays Webster’s other commitments: the Reformational suspicion towards the self and an attitude of child-like receptivity towards Scripture. That is harder to decide…

==================================

Follow @WTravisMcMaken

John Webster’s Holy Scripture: A Dogmatic Sketch (Cambridge, 2003) is a carefully argued fugue on one theme: reintegrating the doctrine of Scripture into a properly theological account of God’s saving work. Webster moves Scripture from its station as theological doorman and gives it place with the other main dogmatic foci. Like them, its adequacy depends on God’s act in Christ and not on standards drawn from elsewhere.

John Webster’s Holy Scripture: A Dogmatic Sketch (Cambridge, 2003) is a carefully argued fugue on one theme: reintegrating the doctrine of Scripture into a properly theological account of God’s saving work. Webster moves Scripture from its station as theological doorman and gives it place with the other main dogmatic foci. Like them, its adequacy depends on God’s act in Christ and not on standards drawn from elsewhere. This also means that, rather delegating exegesis to general hermeneutics, Webster fleshes it afresh along more specifically Christian lines. As such, Webster extends the deeply Reformed tradition of suspicion towards the idolatrous self. “Reading Scripture is an episode in the history of sin and its overcoming; and overcoming sin is the sole work of Christ and the Spirit. The once-for-all abolition and the constant checking of our perverse desire to hold the text in thrall…can only be achieved through an act which is not our own” (89). Critical methods, then, represent for Webster “a false stance towards Scripture,” characterized not by child-like “teachableness” but by “mastery” (102).

This rings true to me. And yet I am also left wondering where this classical tradition of suspicion towards self and the modern legacy of suspicion towards Scripture intersect. Webster acknowledges the “creatureliness of the text” – mildly endorsing modern insights into the Bible’s complex development and gradient historicity (20). But it is hard to imagine what role various forms of ethical criticism could play in his proposal. How might one assume a childlike posture towards the Bible while also recognizing its pervasive patriarchy or class interests?

If Webster would give me no answer, perhaps others who shared his dialectical coordinates might. I turned to the chapter on the Bible in Helmut Gollwitzer’s Introduction to Protestant Theology (trans. David Cairns; Westminster John Knox, 1982). Gollwitzer’s (far shorter) presentation on the doctrine of Scripture addresses two problems: first, of biblical authority per se, and second, of the Bible’s material adequacy to function as authoritative.

Gollwitzer asks in the first instance whether claiming biblical authority effectively places some people (the biblical authors) in power over others (the churches). Is kyriarchy ingredient in biblical authority? The concern does not emerge from a secular egalitarianism; one of Gollwitzer’s fundamental convictions is that the gospel means freedom – spiritual and this-worldly. Can the Bible truly promote human emancipation if its adherents insist that its particular collection of human voices function as an unsurpassable court of theological appeal?

Gollwitzer postpones this question to ask a second: even if biblical authority per se is acceptable, is the Bible capable in the modern period of fulfilling its role as theological arbiter? Here Gollwitzer rehearses the familiar difficulties generated by biblical criticism, namely, the Bible’s gradient historicity and theological plurality.

Gollwitzer responds to these two questions by developing the interlocking concepts of faith and of witness. Faith in the biblical sense is “personal trust in God” (50). It cannot depend on the prior fulfillment of certain conditions, “namely, the act of submission to a human authority, either that of the church’s teaching office (the pope) or that of the biblical authors” (ibid). No human power must be confused with God’s word in which Christians put their personal trust. “By such investing of the Bible with divine authority, by laying down the previous condition of a work to be performed by us…as coming before trust in God’s word addressed to us, we involve ourselves in a hopeless contradiction with what the bible itself has to tell us about the nature of faith” (ibid.).

Rather, the Bible is a witness. Gollwitzer explains the Bible’s similarities in this regard to the church. The church, too, is deeply fallible, theologically disunited, and inevitably local in its history, point of view, and form (56). Yet God uses the church effectively to bring people to faith in Christ. And the church is united by its shared referentiality: in fact, its only unity may exist at the level of its common gaze upon Christ. So, too, is the Bible fallible, disunited, and local; its unity, too, is not formal but referential, pointing to Christ. Two features distinguish it from the church: its uniquely intensive authenticity to its message and its historical proximity to the events of God’s revelation. As a matter of experience over time, the church has found that these writings “thrust themselves” on the community, i.e., their trueness to God is self-attesting (54). The (relative) nearness of their writers to God’s acts of self-revelation in Israel and in Christ also sets them apart from other, subsequent ecclesial forms of testimony.

Gollwitzer’s deployment of these concepts, faith and witness, establish a strong differentiation between the Bible and the word of God, first from the human perspective and then from the divine. Christians trust God (and not, ultimately, the Bible); and God speaks (not, ultimately, the Bible). This distinction enables Gollwitzer to countenance a greater suspicion towards the Bible than Webster’s language about “creatureliness” allows. He goes so far as to encourage exegetes to point out “accommodations [in the biblical texts] to class interests” (60). Gollwitzer thus speaks not only of the Bible’s fallibility in matters of historiography, but also in ethics. Presumably this willingness to identify the interference of class interests could extend to include other forms of ethical criticism, e.g., feminist.

Most likely Webster would find that Gollwitzer’s use of “witness” as an organizing concept falls prey to “a curious textual equivalent of adoptionism,” i.e., it makes the relation between text and revelation too occasional, even arbitrary (24; one wonders if the fallibility of the scriptural witness is a purely formal acknowledgement on Webster’s telling, and authorizes no concrete examples). More important, perhaps, is the possibility that Gollwitzer’s project betrays Webster’s other commitments: the Reformational suspicion towards the self and an attitude of child-like receptivity towards Scripture. That is harder to decide…

==================================

Follow @WTravisMcMaken

Comments

It seems like the same could be said for Barth. He recognizes that the Bible is capable of any sort of error, but which is followed soon thereafter by Barth's caution that we have no objective ground upon which to adjudicate between texts (including an assumed christological ground). The result is that Barth's exegesis, albeit highly creative and often eccentric, is rather conservative vis-à-vis textual authority and biblical integrity. So, while Barth rejects inerrancy, examples are rather hard to come by. Personally, I don't really have a problem with this, so I am just noting the similarity to Webster.

für Barth ist es einfach unmöglich, die Sache, um die es Paulus geht, den Geist Christi von den ‘jüdischen, vulgärchristen, hellenistischen und sonstigen’ ‘Geistern,’ die in Römerbrief auftauchen, zu trennen…Alles ist litera, Stimme der andern Geister und – ob und inwiefern Alles etwa auch in Zusammenhang der ‘Sache,’ als Stimme des spiritus (Christi) verstanden werden kann.

Given this reality that both you and Jaspert observe -- namely, Barth's (and Webster's) willingness formally to acknowledge scriptural fallibility but practically never to sunder the word from the words -- I find it very intriguing that Gollwitzer wrote as he did. How is it that the man whom Barth nominated to succeed him at Basel held the views he did?

Also, my entire reason for getting into this at all is exegetical -- maybe even pedagogical. What am I to tell myself (and students) as I delve into ethical criticism of the Bible? Shrug it off as symptomatic merely of an unteachable and un-docile attitude towards Holy Scripture?

So, for instance, Barth everywhere assumes the results of historical-critical research. But then he goes right ahead and explicates the logic of the narratives "as if" in order to get at their proclamation. Just because he doesn't spend time on historical reconstruction hardly seems relevant to me.

Furthermore, there are numerous times (my CD is at the office or else I'd try to find some) where he takes the results of historical-critical research as starting-points for theological reflection - for instance, by using those results to identify what is truly at stake in the text.

This may not get us all the way to the sort of "ethical" criticism that we find in Gollwitzer, but it does explain a bit more in how HG can come from KB.

I hope that made sense. I'm just dashing this off...

Thanks for the Jaspert quote. I am rather committed to Barth and Webster's doctrine of Scripture, with perhaps a slightly greater interest in the ancient literary culture and the contingencies of such. Fortunately for myself, I am not especially vexed by the moral quandaries of the conquest narratives, among other examples. I obviously recognize the difficulty and encourage open discussion, much less would I attempt some sort of theodicy in defense. Yet, on this, I still stand with the mainstream of evangelicalism, even if I part company on inerrancy. I cannot bring myself to say that God is severely distorted in this or that presentation or attribution in Scripture. At that point, I would wonder why even call it Scripture? (other than pragmatic considerations or ecclesiastical deference) And, as you can guess, I am not (yet) convinced that Jesus' "but I say to you" statements are quite as radical as liberals assume.

Having said that, this is not a hill that I am ready to die on. I will remain open to learn more and correct my theology if necessary.

As for Travis' note, yes, Barth does appear to assume HC results throughout, as when he will reference "P" or "deutero-Isaiah." Of course, a modicum of "historical reconstruction" is assumed by nearly every biblical scholar to be necessary for rightly exegeting the text and rightly grasping its meaning, so Barth's neglect of this has not endeared him to the guild. For example, the imago Dei in Gen 1.26-27 is interpreted, according to standard historical criticism, in light of the overall Priestly theology and concerns, its time and setting, and likely an oral prehistory; meanwhile, Barth does an almost purely theological reading, worthy of patristic exegesis, wherein the imago Dei conforms to Barth's whole theology of other-in-relation, focusing on the sexual binary. I recently did an exegetical paper on this passage, and I can assure you that Barth's interpretation is far outside the ballpark of acceptable exegesis in biblical studies (with the notable exception of Westermann's sympathetic treatment of Barth in W's commentary on Genesis 1-11). I only mention this to highlight that, even though Barth was fairly comfortable with the broad results of HC (namely matters of relative consensus), he does not often use it constructively for his own exegesis, though apparently you have some passages in mind where he does.

It seems to me that the real question here is how historical criticism is related to sache-criticism. I would tend to think of it as a necessary precondition - doing the historical criticism helps you get a clearer picture of the sache at issue. But whether or not you deploy the fruits of historical criticism directly to the dogmatic / ethical task seems secondary to me as since it is an entirely ad hoc question.

Coincidentally, I'm not committed to defending every instance of Barth's exegesis. I doubt he would be too...

As for HG, I think what he is making space for is something like sache-criticism with a socio-political cum contextual horizon. Barth was certainly capable of this, even if there isn't a ton of it obviously in the CD (I think more is there hiding under the surface than is sometimes recognized).

As for your panning of HG's dogmatics, Kevin...

*tsktsktsk

I don't know how you can make this sort of claim: "a fairly generic presentation of commonplace dialectical moves"

It seems to me that dialectical theology is anything but commonplace.

HG was appointed to the position but the Swiss government intervened to prevent that. It was quite the scandal.

As for HG, I think what he is making space for is something like sache-criticism with a socio-political cum contextual horizon.

Yes, that sounds right. That's a good way to describe it.

It seems to me that dialectical theology is anything but commonplace.

True, I was thinking relative to that world. Besides, in Gollwitzer's world, it was commonplace enough.

As for the Torrance bit, I wish I could remember the main source where I read it. From what I read, Torrance was the first asked by Barth to succeed him at Basel, but Torrance rejected the offer (so TFT was never technically nominated). It was a tough decision for Torrance, but he was already settled in Edinburgh and his kids were doing well in the schools. From what I read, it was considerations of his family that most influenced him to remain in Edinburgh.

Also, Dr. Currie at Union-Charlotte, a doctoral student under Torrance at Edinburgh in the 70's, has told me as well that Torrance was asked to succeed Barth, but I do not know if Currie was relaying this directly from Torrance. Anyway, it seems like an odd thing to fabricate.

All I'm saying is that I'd someday like to find the letter from KB to TFT.

That would be an interesting letter to see, if it still exists. If you know any grad students at Edinburgh, you can ask them to investigate.

As for TFT, his papers are in Princeton. I just haven't had a chance to get at them.

As for TFT's papers, Iain brought them to Princeton during his presidency.

It does all boil down to “faith,” but the key issue is “faith in what?”

As far as exegesis is concerned, the results of Gollwitzer’s approach can only be the barrenness of the various ideological criticisms that have come to afflict the church’s reading of its Bible. I personally sense a direct connection between this robbing of Scripture’s ontological ground and the spiritual catastrophe that is the present Protestant state church in Germany.

Big statements, perhaps, so feel free to shoot me down.

I do wonder if you've collapsed Gollwitzer a little too neatly back into Bultmann. You may well be right that the way Helmut spins Sache departs from Barth (later Barth?)-- it offers less/no CONTENT ("undefined" as you put it), is more an event (?? BTW, incidentally, I wonder if you've read Ben Sommer's piece entitled "Revelation at Sinai"; he develops an "actualist" understanding of Scripture from a uniquely Jewish angle). But so far as I know, the critical norm for Bultmann's practice of sachkritik was always the present-tense proclamation of the gospel (or something like that) -- and he did not appeal to general ethical failings of scripture as Gollwitzer does in the chapter under consideration.

I wonder, too, what you (and other readers) make of places in Barth's corpus where he admits of Scripture's fallibility, even in matters of theology and religion. I don't have Strange New World before me, but I think he does there at least. Again, the air around DET is thick with Barth expertise, so I will direct that one to others more knowledgeable than I. Is this just a flourish? What IS this kind of acknowledgement?

Second, what then to do with ethical criticism? Once again my primary interest here is as an exegete: what am I to do in the post-Mieke Bal era? An earlier draft of this post pointed up the fact that Barth and Childs et al responded to a crisis of biblical authority occasioned largely by erosion of confidence in the Bible's uniform purchase on empirical history. But that is no longer the lead cause for doubt in biblical authority these days: now we face an ethical challenge. Barren it may be, but ideological criticism does not disappear with a shrug. And to date, I have found precious little from the Childs school to help me in this quandary. At least Walter Moberly treats Regina Schwartz (for example) as a serious interlocutor.

I am honestly perplexed when you say that "first order dogmatic considerations need to play a role in working out a Biblical hermeneutic from the outset." I am perplexed for a couple reasons. First, where exactly do these dogmatic considerations come from? If they come from the text, then we still have the same hermeneutical dilemma. If they come from the "Great Tradition" or regula fidei, then you've escaped the hermeneutical problem by simply conflating divine revelation with the church in a way that raises a whole host of other theological problems (and which Barth fundamentally opposed). If they come from somewhere else (e.g., a new revelation of the Spirit, as in pentecostalism), then we introduce a whole new set of theological problems.

Second, when you talk about the gap between "witness" and "reality," are you speaking about the gap between the biblical text and the divine reality to which it points? If so, then I cannot understand how your comment claims to be an explication of Barth's position. For surely you must know that he makes one of the clearest and sharpest distinctions between text and reality. To be sure, the scripture is part of the threefold form of the word of God, but it is precisely the second of three forms by virtue of the way it points away from itself toward the reality of Christ, which is qualitatively distinct from the text. Indeed, your appeal to Barth's doctrine of the threefold word here is very odd, since this doctrine serves precisely to undergird a responsible Sachkritik. The Sache here is the first and central form of the word, namely Christ himself, and this distinction funds Barth's critical exegesis of the text. The Sache that is Christ becomes the hermeneutical key for understanding the genuine message within a fallible and historically situated document.

Third and finally, Bultmann has the same Sache as Barth. I don't have time to demonstrate this at length, but I can show you passage after passage to confirm this. He doesn't make some nebulous "existential stance" into the Sache. It is quite explicitly the kerygmatic Christ, the "Christus praesens," who speaks to us in and through the text, that functions as the normative Sache for interpreting the biblical text. Is there a difference between Barth and Bultmann here? Yes, because they flesh out their christologies in different ways. But the fact that Christ is the hermeneutical norm remains the same.

If we want to debate their respective christologies, that's fine. But let's not dismiss Bultmann or Gollwitzer for not presupposing some kind of dogmatic theology as the basis for interpretation. I would strongly question whether even Barth does that, and I'm generally critical of Barth on these issues. It sounds like what you want is an exegesis controlled in advance by a dogmatic presupposition, which would be extremely dangerous.

Collin,

I probably have collapsed Gollwitzer into Bultmann. I’ve never read the man (G) so I know nothing about him. I was primarily providing a gut reaction to what I felt was the tendency of what you were writing about him, which reminded me of Bultmann.

As for Barth and (theological) infallibility, I kind of get the impression that he was open in theory to bits of the Bible not in fact truly pointing to God but that in practice he himself never saw where that might have been the case. But I’m by far not a Barth expert. The Childsian version is also interesting—if I’ve understood him right (this is a difficult area). He also is open in principle to portions of the Bible not pointing to the reality of God. For this reason he talks about the “search for the Christian Bible” as being a central task of the theology (in BTONT). But at the same time it seems that for him the fuzzy grey area lies somewhere outside the boundaries of the Hebrew version of the text (not sure what he thinks about the NT, though I don’t think the boundaries are quite as disputed there). The MT appears to represent a stable core for him whereas the value of the Greek language apocryphal books is less certain. The reason why he seems to go for the Masoretic Text as a bare minimum is because that is the collection identified by the Jews, and he believes that the Jewish people are the authoritative “tradents of the tradition” (referencing Jerome on that). The church ought to take the MT as its authoritative basis in order to preserve the “ontological unity of the people of God.” He doesn’t try to prove this point objectively or by referring to external criteria—which is probably due to his similarly actualistic understanding of revelation and his commitment to the idea that gospel truth is “self-authenticating.” In the end, Childs would say that we must just situate ourselves in a church tradition and from that standpoint search and pray (faith seeking understanding; for an example of him saying this, see his thoughts on the textual criticism of the New Testament at the end of his Intro to the NT). I’ll say more on this to David below, though it’s an area I still need to get my head round.

Concerning the “ethical challenge” to the inspiration of the Bible: all ethics is grounded in prior assumptions of a theological nature, assumptions about the nature and will of God, the nature of the universe and the nature of humanity. So the question is what theology/ideology is driving the critique? To be truly “sach-critical” in my mind, the ethical norm would have to be informed by the “substance” (= Sache) of the whole canon of Scripture, and that in turn requires a circular reading (from reality to witness and back again). Incidentally, on a canonical approach the Bible itself already provides the means by which its ethical content is to be extracted—something routinely overlooked by ethical critics of the Bible (it seems to me). That is the inter-relation between narrative and law that characterizes the entire Pentateuch, for example, and is hermeneutically normative (note Jesus’ reference to creation to interpret the law on divorce). So the very form of the text invites us to interpret law in terms of its telos (i.e. the “spirit of the law”), which is itself perceived when that law is read in the light of the broader Biblical narrative, which is the “Sache” (I can say that as I go for a very “narrative” understanding of the Sache—as Barth does when he says that God >is< a Geschichte [in Dogmatik im Umiss]; though I’m indebted to Robert Jenson).

In short, my response to an ethical critic would be this: encounter the reality brokered by the full canonical shape and read the ethics of the Bible in light of that, and then see what happens. That is “sach-critical” and it is also canonical, respecting the contours of the final form.

Thank you very much for your well-thought out and well-presented response. You say you are “honestly perplexed”; I didn’t think what I wrote was confusing—though the subject matter is certainly complex—so I hope this clarification helps. Please do keep pushing me if what I’m saying doesn’t help or is just dumb.

First, how do we get to these dogmatic considerations? The same way Gollwitzer got to his statement about the nature of “faith”: by entering the hermeneutical spiral and reading the Bible to let it shape our broader convictions, even while our broader convictions both illumine and constrain our interpretation. And we do that by consciously participating in the church tradition we associate with. This is certainly not absolutely secure, an objective path to knowledge, but then objective knowledge is not what the God who inspired these texts is interested in communicating anyway. What he wants is vertical encounter in horizontal community that leads to praise and obedience. I think this is just “faith seeking understanding.” My problem with Bultmann’s approach (not enough has been said about Gollwitzer here for me to comment) is that he seems more indebted to Heidegger than to the church tradition in which God—to some greater or lesser degree but surely always faithfully—has been involved. I remember my bewilderment when reading Eschatology and History at how he gets to his basic starting point: he reads a bunch of ancient historiography and decides that the thing really driving all these writings is the question of “man’s existence” (really?). That, then, becomes his canonical means of extracting the substance of Christian scripture as well: surely what is driving these texts is the question of our existence and that is what must be extracted. It seems he was doomed from the outset. Though you’re knowledge of Bultmann is far more sophisticated than mine (as some of your comments indicate; see below), so I’m happy to be corrected here (plus I’m writing now from memory: it’s been two and half years since I last read the man).

So, yes, the “hermeneutical problem,” as you put it, remains if what we are looking for is an objective starting point that does not require us to take up a stance within a particular tradition and trust that all our endeavours—including our exegetical ones—are only of significance to the degree that they are acts of obedience in the Spirit as God works out his plan of salvation in the here and now. But that is not God’s modus operandi and it is completely alien to the form and content of Scripture we’re trying to interpret.

Also: affirming the value of the (or a) regula fidei, something Barth seems to have done (I don’t know how tentatively—I’m thinking of his comments on creeds in his Einführung/Introduction) but Childs certainly did, does not necessarily mean conflating revelation with the church. For Childs, at least, the two relate dialectically as they mutually inform each other, though he would always affirm that the Scripture should be able to critique church formulae. I think it is anathema to believe interpretation must always start from a clean “pre-creedal” slate and work slowly towards building up a pristine doctrinal system. It belongs to the shape of the divine economy that we are always already thrown in the midst of things—and from that messy starting point seek to read the text within the broader context of the ongoing struggle of the church to collectively identify and follow the will of God.

Finally (on this point): why is a theological (even ontological [Trinitarian]) framework more adequate as one pole of the exegetical dialectic between text and Sache than existential philosophy? Because of the nature of the text: it is theocentric, and the God it points to wishes to be known. He has made himself known as the Trinity. That is the Sache and, as people like Jenson demonstrate, it is hermeneutically incredibly fruitful.

So again: first order theological-ontological considerations ought to play a decisive role in working out a proper hermeneutic of Scripture (and definition of its nature). And this is surely very Barthian.

I totally agree with this statement of yours: “The Sache that is Christ becomes the hermeneutical key for understanding the genuine message within a fallible and historically situated document.” Except that I think the substance of Scripture is the Trinity and not Christ per se (see Chris Seitz’s debate with F. Watson). And I get the impression that that distinction is important for differentiating Barth from Bultmann (who had no interest in thinking about God’s being, oddly assuming—as he put it in the intro to his NT theology—that the humanness of the text somehow hinders us from getting to the “sache” of the text, requiring us to engage in anthropology rather than theology [again please do correct me if I’m oversimplifying]).

This naturally brings me to your final point about Bultmann having the same Sache as Barth. I do find your comment that for Bultmann it is the “the kerygmatic Christ, the "Christus praesens," who speaks to us in and through the text” fascinating. I have to admit, I have not come across that idea, though I have only read two of his books and the intro to his Intro to the NT (not much, perhaps). Could you give me a good example of where to find it?

Nevertheless, I suspect that the Christological difference between Bultmann and Barth is very significant for the point being made here, namely that first order theology is hermeneutically significant. It’s one thing to say that “Christ” is the hermeneutical key, but of course the key issue is “who is that Christ?” Barth’s Christ is the Son of God who sends us his Spirit. That small “dogmatic” detail, as I hope I have shown, has profound hermeneutical implications.

Thanks for taking the time, David and Collin. Please do feel free to point out where I’m missing something. I’m one of those weirdoes who doesn’t mind being told he’s wrong or inconsistent.

Thanks for the clarifications. That's very helpful. So I think it's best if we separate the Bultmann-interpretation from your own Childs-inspired position. So let me go in that order.

You raise a lot of objections to Bultmann, most of which are standard and understandable criticisms, given the idiosyncratic way that Bultmann often spoke. I'm tempted to say "go read my dissertation," since I'm effectively just going to repeat what I say there in my response to you, but without going into nearly as much detail. This will be the Cliff's Notes version.

1. Bultmann has almost no indebtedness to Heidegger, as surprising as that will sound. Indeed, all of his material decisions are made prior to encountering Heidegger; Heidegger actually read Bultmann before Bultmann read Heidegger, so the influence may very well be in the other direction; Heidegger provides Bultmann with formal concepts but that's it; and at every point that Heidegger transgresses a limit determined by the material norm of theology, Bultmann objects. So Heidegger is of no material significance where Bultmann's theology is concerned. (This is not a new thesis. Roger Johnson made the case for it in 1974, and the publication of Heidegger's Nachlass in the years since has confirmed it.)

2. Bultmann explicitly appeals to the tradition of the church as the starting-point for Christian theology. I may have given the wrong impression when I criticized appeals to tradition. Bultmann is quite clear in 1925 that the “concrete situation” for exegesis is “the tradition of the church of the word.” Since “I stand in my existence in the tradition of the word, there is a readiness for faithful questioning.” And in 1929 Bultmann says that the communication of the church “belongs itself to what is communicated,” since it is not a “mere conveying” of facts but rather a word that addresses each person. The church’s teaching “has the character of tradition, which belongs to the history that it narrates. The tradition belongs to the event itself.” I could go on, but the point is that Bultmann affirms that the gospel message includes the tradition. The only question, of course, is in what sense. How are we to understand the way in which kerygma and tradition relate?

4. As you admit, you have not read much of Bultmann's work. If you want to see where he develops these ideas, take a look at my reading guide to Bultmann that I posted recently on my blog. You can find all you need there. I would also recommend the book Christus Praesens by James F. Kay, which is probably the best book on Bultmann's christology.

1. There is a false dichotomy that I discern in your comment about the regula fidei. You seem to suggest that we have two options: either (a) starting from "a clean 'pre-creedal' slate" and building up to a full theological system or (b) presupposing the received tradition as normative. I reject both options. It all depends on responsibly and clearly differentiating between kerygma/gospel and text/tradition. The normative Sache encounters us in and through the text and its traditions without ever identifying itself with them. There is indeed something "pre-creedal" that is not some ahistorical blank slate. The tradition of Christian faith cannot and must not be identified with the dogmatic creeds that are a historically situated translation of the eschatological message of Christ. The received tradition is only truly tradition, i.e., the handing-on of the faith, insofar as it becomes, in the moment, the medium of God's speech to us. It is not in itself the bearer of this message.

2. Staying on this theme, let's turn to the witness/reality problem. Here is where we truly disagree -- and perhaps fundamentally so. You write: "I am not saying (that Barth etc. says) that there is no gap, but I am saying that gap is 'bridged,' and that happens pneumatologically. To use Childs’ phrase, the text is 'infused with its full ontological reality...'" Notice the apposition of "pnematologically" and "the text." This indicates where you side with the postliberalism of Childs over against the actualism of Barth and Bultmann. For the latter, the work of the Spirit does not occur in the text itself but in the encounter with the text here and now. The text is never "infused" with anything; it is a fully human document that simply attests what particular people and communities understood about God. The reality never becomes a property of the text, nor does it become a property of the reader. Instead, the text becomes the medium of God's speech when and where the Spirit illuminates the reading of it, which occurs when and where we hear the kerygma as a message that concerns us. And this encounter with the reality of God occurs again and again, ever anew, so that we cannot speak of a gap being "bridged." Indeed, we can only really speak of a "bridging" ever anew. But I think we have to dispense with gap language altogether. The gap only exists on the human side, and that's simply because of the ontological differentiation between creature and creator; it is nothing unique to the text. On the divine side, there is no gap at all, because God is noncompetitively present in the world. God is paradoxically identical with the creaturely factors that become the sites for the human encounter with Christ. So on the divine side, there is no "gap" to cross; on the human side, the distinction between reality and witness remains even in the moments of paradoxical identity (i.e., it remains paradoxical), simply because God can never be objectified as something available at hand.

4. "I totally agree with this statement of yours: 'The Sache that is Christ becomes the hermeneutical key for understanding the genuine message within a fallible and historically situated document.' Except that I think the substance of Scripture is the Trinity and not Christ per se (see Chris Seitz’s debate with F. Watson)." Two problems. First, the Sache is not "the substance of scripture." It is the living Christ himself in his kerygmatic encounter with us. Second, I reject any distinction between trinity and christology regarding the Sache. Such distinctions trade on what I consider to be a false understanding of the trinity. The Christ-event in its historical actuality is the being of the trinity: the Father is the one Jesus experiences as the power of his sending, while the Spirit is the one Jesus experiences as the power of his mission. This historical event simply is the eternal trinity. Also, Bultmann has no aversion to thinking about God's being, once we understand that this being is not something above or prior to God's actions in history. I discuss this at length in my dissertation and describe his position as an "eschatological theological ontology."

Thanks for the interesting conversation.