Should We Speculate on the Fate of the "Unevangelized"?

I began this series with an overview of an older but well-worn book by John E. Sanders that contributes significantly to an evangelical theology of religions. To review: Sanders asks what, as Christians, we can say about the fate of those who never hear the Gospel of Jesus Christ explicitly proclaimed, or who through some incapacity are simply unable to receive it?

No Other Name: An Investigation into the Destiny of the Unevangelized, by John E. Sanders (Eeerdmans, 1992).

I have to wonder if this is the sort of theological project that someone like me, tainted by Barthianism as I am, might even wish to engage. Perhaps some of you, gentle readers, might have the same question.

I can think of two reasons why I might demur from such a project: On the one hand, why should I commit to anything that bills itself as an evangelical theology in the first place? Nowadays -- and I scarecely need to point this out to most of you -- the question of evangelical identity is particularly fraught and vexed, especially for anyone hailing from a conservative Christian background who has even a modicum of a social conscience (and thank God, many do). Far be it from me to contribute here to the neurotic hand-wringing that pervades this topic.

Am I an evangelical in the contemporary North American sense, anyway -- albeit a poor one, corrupted by reading Schleiermacher and higher biblical criticism? Perhaps such questions are best left to the eschaton.

Still, there is another reason one might give a project such as Sanders' one a miss. Maybe the whole business is pointless speculation. We have our marching orders -- share the Gospel! -- and perhaps we shouldn't agitate our puny mortal neurons with such high-minded matters. Perhaps theologians should embody the humility of the Psalmist: "Lord, I am not high-minded. I have no proud looks. I do not exercise myself in great matters which are too high for me" (Ps. 131:1-2, Book of Common Prayer, 1928).

For my part, I find it refreshing, if also somewhat frustrating, when theologians admit they don't know what we're even talking about. If only a certain chief executive and his spokespersons ever showed such reticence! Perhaps on the question of what awaits the unevangelized, we should practice a "reverent agnosticism." Sanders quotes evangelical luminary J.I. Packer on this issue:

Now Packer has written or co-authored something like 60 books, so he's not necessarily mum in the face of mysteries, in the Wittgensteinian sense. Yet his rejoinder to this inquiry no doubt would be: Where scripture is silent, we should be as well. But isn't Packer making a larger point here? Perhaps having "very little theology" is not such a bad thing? Aren't there enough practical enigmas and problems in this world to keep our plates full until humankind destroys itself, an asteroid decimates our atmosphere, or the sun explodes -- whichever comes first? And assuming the question of the fate of the unevangelized is existentially significant -- and for the sake of argument let's concede that it is -- how can we even begin to answer such a question?

Don't "biblical" Christians, after all, trust that God is just and will do the right thing? Of course, Sanders writes, but he thinks we can do more than shrug our shoulders at this question. He argues that we can and indeed must attempt an answer if our message and mission as Christians is to have any credibility. He writes:

For my part, I take Sanders' side of this debate. Whether or not one agrees with his own solution (a "wider hope" theory) or one of the other historical viewpoints he surveys, we as believers must take some sort of stance on the question of humankind's ultimate destiny, including what we might hope from the love and power of God revealed in Jesus Christ, as attested in scripture and recapitulated in worship and tradition. Still, what are the epistemic conditions for the possibility of even posing a plausible and compelling response to the question of our hopes for the "unevangelized"? To address such issues, as Sanders does, we need to untangle the knots of biblical hermeneutics and sift through the history of Christian thought.

I'm beginning to expect this series may take a little while.

==================================

Follow @jsjackson15

No Other Name: An Investigation into the Destiny of the Unevangelized, by John E. Sanders (Eeerdmans, 1992).

I have to wonder if this is the sort of theological project that someone like me, tainted by Barthianism as I am, might even wish to engage. Perhaps some of you, gentle readers, might have the same question.

|

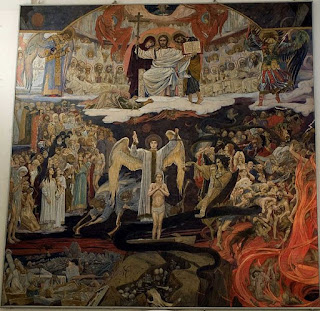

| The Last Judgment, by Viktor Vasnetsov (1904) Photo by Scatestle (Via Wikimedia Commons, PD-1994) |

I can think of two reasons why I might demur from such a project: On the one hand, why should I commit to anything that bills itself as an evangelical theology in the first place? Nowadays -- and I scarecely need to point this out to most of you -- the question of evangelical identity is particularly fraught and vexed, especially for anyone hailing from a conservative Christian background who has even a modicum of a social conscience (and thank God, many do). Far be it from me to contribute here to the neurotic hand-wringing that pervades this topic.

Am I an evangelical in the contemporary North American sense, anyway -- albeit a poor one, corrupted by reading Schleiermacher and higher biblical criticism? Perhaps such questions are best left to the eschaton.

Still, there is another reason one might give a project such as Sanders' one a miss. Maybe the whole business is pointless speculation. We have our marching orders -- share the Gospel! -- and perhaps we shouldn't agitate our puny mortal neurons with such high-minded matters. Perhaps theologians should embody the humility of the Psalmist: "Lord, I am not high-minded. I have no proud looks. I do not exercise myself in great matters which are too high for me" (Ps. 131:1-2, Book of Common Prayer, 1928).

For my part, I find it refreshing, if also somewhat frustrating, when theologians admit they don't know what we're even talking about. If only a certain chief executive and his spokespersons ever showed such reticence! Perhaps on the question of what awaits the unevangelized, we should practice a "reverent agnosticism." Sanders quotes evangelical luminary J.I. Packer on this issue:

[I]f we are wise, we shall not spend much time mulling over this notion. Our job, after all, is to spread the gospel, not to guess what might happen to those to whom it never comes. Dealing with them is God's business (p. 16)

Now Packer has written or co-authored something like 60 books, so he's not necessarily mum in the face of mysteries, in the Wittgensteinian sense. Yet his rejoinder to this inquiry no doubt would be: Where scripture is silent, we should be as well. But isn't Packer making a larger point here? Perhaps having "very little theology" is not such a bad thing? Aren't there enough practical enigmas and problems in this world to keep our plates full until humankind destroys itself, an asteroid decimates our atmosphere, or the sun explodes -- whichever comes first? And assuming the question of the fate of the unevangelized is existentially significant -- and for the sake of argument let's concede that it is -- how can we even begin to answer such a question?

Don't "biblical" Christians, after all, trust that God is just and will do the right thing? Of course, Sanders writes, but he thinks we can do more than shrug our shoulders at this question. He argues that we can and indeed must attempt an answer if our message and mission as Christians is to have any credibility. He writes:

It is true that our primary task ought to be following Jesus and spreading the good news of his kingdom to all the world. But accomplishing that task involves the theological activity of answering new questions as they arise. If we did not speculate about subjects not directly revealed in the Bible, we should have very little theology; we would have no doctrine of the Trinity, no doctrine of Jesus having both a human and divine nature in hypostatic union (p. 17).

For my part, I take Sanders' side of this debate. Whether or not one agrees with his own solution (a "wider hope" theory) or one of the other historical viewpoints he surveys, we as believers must take some sort of stance on the question of humankind's ultimate destiny, including what we might hope from the love and power of God revealed in Jesus Christ, as attested in scripture and recapitulated in worship and tradition. Still, what are the epistemic conditions for the possibility of even posing a plausible and compelling response to the question of our hopes for the "unevangelized"? To address such issues, as Sanders does, we need to untangle the knots of biblical hermeneutics and sift through the history of Christian thought.

I'm beginning to expect this series may take a little while.

==================================

Follow @jsjackson15

Comments