Thomas Cranmer - Know When to Hold 'Em, Know When to Fold 'Em: #Refo500atDET

Remember that old Kenny Rogers song where Kenny (I presume) meets a gambler on a train bound to nowhere? After bumming a ciggy and Kenny’s last swig of whiskey, the gambler shares an important life lesson he’s learned in plying his trade.

He says:

I begin with this because the career of Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556), the great “architect of English Protestantism,” can be seen, among other things, as a proleptic anticipation of Kenny Rogers’ “The Gambler.” To make any real progress in the tumultuous political environment of 16th century England, the Reformation needed someone like Cranmer — someone who knew how to play the game.

---------------------------

As a bright young scholar and churchman, Cranmer belonged to a contingent of Lutheran sympathizers in Cambridge in the 1520s. Their regular meeting place, The White Horse Inn, was dubbed “Little Germany.”

King Henry VIII was no friend of the Reformation. He was a committed Catholic who was personally invested the theological developments happening on the Continent. In fact, in 1521 he even published an anti-Lutheran diatribe titled “Assertion of the Seven Sacraments,” for which Pope Leo X awarded him the title “Defender of the Faith.”

This is why, although Henry is notorious for his many bedfellows, Cranmer was certainly one of the strangest.

---------------------------

Henry found himself in a predicament in the later 1520s when he decided that he wanted his marriage to Catherine of Aragon annulled. Worried that he and Catherine’s failure to produce a son was a sign of God’s judgment upon their marriage (she was the widow of Henry’s elder brother, which appeared to render their marriage problematic according to Leviticus 18:16), and concerned that without a male heir the country might again be plunged into civil war upon his death, he asked Pope Clement VII for the annulment. The fact that he also happened to have the hots for Anne Boleyn at this time made Henry's decision even easier, of course.

This put Pope Clement in an incredibly awkward situation. Henry and Catherine had been granted a special papal dispensation to get married in the first place. This meant that granting the annulment would mean contradicting the decision of a previous pope at a time when papal authority was being severely called into question. Furthermore, Rome had just been sacked, and was then being occupied, by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V — Catherine’s nephew. Clement had every reason to deny Henry’s request and, of course, he did.

At this point Henry was determined to find a way of getting around the pope, and that’s where Cranmer came in handy.

---------------------------

Cranmer ended up working alongside Henry’s new royal minister, Thomas Cromwell (another reform-minded individual), to secure Henry’s annulment by appealing to the universities and to the English court. Though reluctant to take the position, Cranmer was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury in 1533. In this new role he formalized both the annulment of Henry’s old marriage to Catherine and his new marriage to Anne.

The Pope, none too happy with this, annulled the annulment and excommunicated Henry. Then, in 1534, Henry passed the Act of Supremacy — which Cranmer and Cromwell had been working on — declaring that the ultimate authority over the church of England resided not with the pope, but with the monarch (that is, with Henry himself).

The Act of Supremacy was a crucial turning point in the story of the English Reformation, but it did not make the English Church Protestant. It was a legal and institutional break from the papacy, and there was enough anticlerical and antipapal sentiment alive among the English people for Henry to pull it off. However, Christianity in England continued along decidedly Catholic lines in official doctrine and in practice.

Nevertheless, for reform-minded Brits like Thomas Cranmer, this was a major step forward. It was a risky hand to be dealt — a King who wanted out from under papal authority, but who harbored deep theological objections to Protestantism, and was none too shy with the axe. Chancellor Thomas More actually lost his head over all this business, being too intransigent, too much a man of principle, to play savvy when the cards were against him.

What Cranmer’s true thoughts were regarding the annulment is impossible to say. We do know that by the time he was appointed Archbishop he had already spent significant time in Nuremberg with the Lutheran Theologian Andreas Osiander, where he further solidified the Protestant convictions he had picked up in Cambridge. He even married Osiander’s niece, Margaret, though he had to keep her a secret after being called up to the archbishopric (clerical celibacy still being the law of the land).

What’s clear from all this is that Cranmer knew how to read Henry. He had a good sense for what he could get away with and what he couldn’t. He knew how to pick his battles. Though it would put him in a sticky situation at the end of his life, one important thing he had going for him was his earnest commitment to the notion of Royal Supremacy. It was just the thing he needed to ingratiate himself to a desperate king in need a way of circumventing the papacy.

This push to bring the Church of England out from under the auspices of Rome was Cranmer’s first big gamble. He played his cards well, and he gained a position of influence from which to advance an incremental reform agenda in the years to come.

---------------------------

Now the cards had been reshuffled.

After the Act of Supremacy, Henry needed new political allies and he began looking to the German Lutherans. This provided, as Carter Lindberg notes, “unprecedented breathing space to Protestantism in England.”

Back in 1530, Henry had William Tyndale’s English translations of the Bible burned. But now, only five years later and at the behest of our boy Cranmer and his colleague-in-reform Cromwell, Henry encouraged English Bibles (based on Tyndale’s translations) to be placed in every church. Henry also dissolved the monasteries and confiscated their land. “What for Cranmer and Cromwell was a pious fraud was for Henry a lucrative source of revenue.”

It was also at this time that Reformation doctrine began to eke its way into the recognized teaching of the English Church. Admission to the Schmalkaldic league was conditional upon acceptance of Reformation doctrine. Working with Lutheran theologians and the Augsburg Confession, Cranmer and his colleagues in the English Church (which at this point included both reform-minded folks and conservatives like Stephen Gardiner and Cuthbert Tunstall) came up with the Ten Articles of 1536. This first statement of faith of the autonomous English Church was a compromise with the Reformation — affirming that justification is obtained by Christ’s merits alone, but also that this is necessarily accompanied by “contrition and faith joined with charity”; affirming the substantial presence of the body and blood of Jesus in the bread and wine of the Eucharist, but eschewing a particular theory explaining that presence. They later became a starting point for Cranmer’s Forty-Two Articles, and for the their consolidation into the Thirty-Nine Articles that were adopted during the reign of Elizabeth I. The following year, in 1537, the so-called Bishop’s Book was published to clarify the teaching of the Ten Articles. On the one hand, it affirmed seven sacraments. On the other, it advanced a more Lutheran doctrine of justification (possibly influenced my Melanchthon).

Henry never quite liked the Bishop’s Book and as alliances with the Germans became less crucial, and negotiations broke down, he sought to impose religious unity (or at least uniformity) along more conservative lines. At this point, at the end of the 1530s, Henry’s religious policy was being influenced more by conservatives like Stephen Gardiner and Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk, than it was by Cranmer — though Cranmer retained his position as archbishop.

This led, in 1539, to the adoption of the Six Articles — which reaffirmed traditional doctrine with respect to clerical celibacy, confession, and most importantly, transubstantiation. It became known as the “whip with ten strings.” These were followed up, in 1534, by the King’s Book (corresponding to the Bishop’s Book), which assigned human beings a level of explicit cooperation with God in attaining justification. There were also restrictions placed on who was allowed to read the Bible in English.

There was quite a bit of heretic hunting in this more conservative period, of both alleged papists and Lutherans. Cromwell met his end during this time, accused of treason and heresy. Another name worth highlighting is that of Anne Askew — a Protestant martyr who was tortured on the rack and then burned at the stake. The strength of her conviction and her courage even in the face of death sets a remarkable example. That being said, her way was not Cranmer’s; and his way had something to commend it as well.

Much in this period must have horrified Cranmer. But he did not have a winning hand, and he knew it. It was time to fold ‘em, to stay alive and bide his time for another deal.

Cranmer was keeping his head down. It would be wrong, however, to suppose that he was out of the game entirely. He was working on a book of homilies. Also, in 1544 and at Henry’s request, he composed a litany in English that would later become the first installment of the Book of Common Prayer — his life’s most influential work.

---------------------------

After Henry’s death in 1547, Protestant holdouts who had been quietly waiting in the wings in the English court were well positioned to take power. Henry was succeeded by his then 9-year-old son, Edward VI,

who had been taught by Protestants and who now had a series of Protestant regents ruling in his place.

Cranmer decided it was time to go all in.

His Book of Homilies countered the King’s Book with a clear and explicit affirmation of the doctrine of justification by grace alone. Through the first and second editions of Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer (in 1549 and 1552 respectively), the English people were introduced to a Reformed understanding of the Eucharist that flatly denied transubstantiation and essential presence in favor of a modified form of Zwinglian memorialism that emphasized a “spiritual reception of Christ in the heart of the believer.” This understanding most closely resembled that of Heinrich Bullinger, Zwingli’s successor in Zürich. In the bread and the wine, believers remembered the once-for-all sacrifice of Christ on the cross and, in doing so, received Christ not bodily but spiritually. Church architecture was quickly changed to reflect the new reformed understanding, with stone alters being replaced by wooden tables (the former indicating a place of sacrifice while the latter a memorial meal).

In 1553, Cranmer’s new Forty-Two Articles of Religion were given royal assent. They outlined some important points of doctrine for the young reformed Church of England, and would later become the basis for the paired down Thirty-Nine Articles under Elizabeth I. His Book of Common Prayer, however — as much a genius compilation of biblical, ancient, and medieval liturgical sources as it was original poetic composition — was Cranmer’s most influential achievement by far.

Alan Jacobs notes:

The core of a Protestant Church of England was therefore established during the reign of Edward VI, with Cranmer leading the charge. Unfortunately for him, Edward did not reign long. Having always been of precarious health, Edward died in 1553. Concerned that all their progress would be lost if Mary Tudor (a firmly committed Catholic) came to the throne, Cranmer joined a conspiracy to deny Mary the succession on the basis of her being “illegitimate” as the offspring of Henry’s “illegitimate” marriage to Catherine. Their plan was to pass the throne instead to Henry’s Protestant grandniece, the young Jane Grey.

For all his calculation and political savvy, here Cranmer overplayed his hand. He had gone all in on a king who, though favorable to Cranmer’s reform program, was not long for this world. The conspiracy was a failure; Mary Tudor took the throne, while Grey and the conspirators were sentenced to death.

---------------------------

The gambler in Kenny Roger’s song meets an almost idyllic end; right there on the train, he crushes out his cigarette and fades off to sleep. Cranmer was not so lucky.

He was imprisoned from 1553 until his death in 1556, and tried for heresy and treason. He was among the nearly three hundred Protestants that Queen Mary burned at the stake in her five short years in power. Before his own execution, Cranmer was made to watch his Protestant friends and colleagues burn. Lacking the kind of courage that was seen in the likes of Anne Askew, he signed a number of official recantations, allegedly reconciling himself to Catholicism. When it finally came time for his own execution though, Cranmer publically affirmed his Protestant convictions, recanting his former recantations, and dramatically holding out the hand with which he had signed the recantations over the flames to be consumed first.

---------------------------

Reformation in England, in the 16th century, was a high-stakes gamble. Cranmer was the man for the job because he knew how to play the game. He did what he needed to do to stay alive, and to make what advances he could. As a result, he had a monumental impact on the direction of the Christian faith in England and, by extension, on the faith experience of millions of Christians around the globe for centuries to come.

Chapman, Mark. Anglican Theology. New York, NY: T&T Clark, 2012.

Jacobs, Alan. The Book of Common Prayer: A Biography. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013.

Lindberg, Carter. The European Reformations, 2nd Edition. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

#Refo500atDET introduction and schedule available here.

==================================

Follow @WTravisMcMaken

Subscribe to Die Evangelischen Theologen

He says:

You’ve gotta know when to hold ‘em,Yeah, if you didn’t before, now you know the song I’m talking about. And if for some odd reason you still don’t, or you just need a refresher, check out the 1978 music video. It’ll enrich your life, and it’ll help you understand Thomas Cranmer.

Know when to fold ‘em,

Know when to walk away,

Know when to run.

I begin with this because the career of Thomas Cranmer (1489-1556), the great “architect of English Protestantism,” can be seen, among other things, as a proleptic anticipation of Kenny Rogers’ “The Gambler.” To make any real progress in the tumultuous political environment of 16th century England, the Reformation needed someone like Cranmer — someone who knew how to play the game.

---------------------------

As a bright young scholar and churchman, Cranmer belonged to a contingent of Lutheran sympathizers in Cambridge in the 1520s. Their regular meeting place, The White Horse Inn, was dubbed “Little Germany.”

King Henry VIII was no friend of the Reformation. He was a committed Catholic who was personally invested the theological developments happening on the Continent. In fact, in 1521 he even published an anti-Lutheran diatribe titled “Assertion of the Seven Sacraments,” for which Pope Leo X awarded him the title “Defender of the Faith.”

This is why, although Henry is notorious for his many bedfellows, Cranmer was certainly one of the strangest.

---------------------------

Henry found himself in a predicament in the later 1520s when he decided that he wanted his marriage to Catherine of Aragon annulled. Worried that he and Catherine’s failure to produce a son was a sign of God’s judgment upon their marriage (she was the widow of Henry’s elder brother, which appeared to render their marriage problematic according to Leviticus 18:16), and concerned that without a male heir the country might again be plunged into civil war upon his death, he asked Pope Clement VII for the annulment. The fact that he also happened to have the hots for Anne Boleyn at this time made Henry's decision even easier, of course.

This put Pope Clement in an incredibly awkward situation. Henry and Catherine had been granted a special papal dispensation to get married in the first place. This meant that granting the annulment would mean contradicting the decision of a previous pope at a time when papal authority was being severely called into question. Furthermore, Rome had just been sacked, and was then being occupied, by the Holy Roman Emperor Charles V — Catherine’s nephew. Clement had every reason to deny Henry’s request and, of course, he did.

At this point Henry was determined to find a way of getting around the pope, and that’s where Cranmer came in handy.

---------------------------

Cranmer ended up working alongside Henry’s new royal minister, Thomas Cromwell (another reform-minded individual), to secure Henry’s annulment by appealing to the universities and to the English court. Though reluctant to take the position, Cranmer was appointed Archbishop of Canterbury in 1533. In this new role he formalized both the annulment of Henry’s old marriage to Catherine and his new marriage to Anne.

The Pope, none too happy with this, annulled the annulment and excommunicated Henry. Then, in 1534, Henry passed the Act of Supremacy — which Cranmer and Cromwell had been working on — declaring that the ultimate authority over the church of England resided not with the pope, but with the monarch (that is, with Henry himself).

The Act of Supremacy was a crucial turning point in the story of the English Reformation, but it did not make the English Church Protestant. It was a legal and institutional break from the papacy, and there was enough anticlerical and antipapal sentiment alive among the English people for Henry to pull it off. However, Christianity in England continued along decidedly Catholic lines in official doctrine and in practice.

Nevertheless, for reform-minded Brits like Thomas Cranmer, this was a major step forward. It was a risky hand to be dealt — a King who wanted out from under papal authority, but who harbored deep theological objections to Protestantism, and was none too shy with the axe. Chancellor Thomas More actually lost his head over all this business, being too intransigent, too much a man of principle, to play savvy when the cards were against him.

What Cranmer’s true thoughts were regarding the annulment is impossible to say. We do know that by the time he was appointed Archbishop he had already spent significant time in Nuremberg with the Lutheran Theologian Andreas Osiander, where he further solidified the Protestant convictions he had picked up in Cambridge. He even married Osiander’s niece, Margaret, though he had to keep her a secret after being called up to the archbishopric (clerical celibacy still being the law of the land).

What’s clear from all this is that Cranmer knew how to read Henry. He had a good sense for what he could get away with and what he couldn’t. He knew how to pick his battles. Though it would put him in a sticky situation at the end of his life, one important thing he had going for him was his earnest commitment to the notion of Royal Supremacy. It was just the thing he needed to ingratiate himself to a desperate king in need a way of circumventing the papacy.

This push to bring the Church of England out from under the auspices of Rome was Cranmer’s first big gamble. He played his cards well, and he gained a position of influence from which to advance an incremental reform agenda in the years to come.

---------------------------

“Every gambler knows---------------------------

That the secret to survivin’

Is knowin’ what to throw away

And knowing what to keep

‘Cause every hand’s a winner

And every hand’s a loser

And the best that you can hope for

Is to die in your sleep.”

Now the cards had been reshuffled.

After the Act of Supremacy, Henry needed new political allies and he began looking to the German Lutherans. This provided, as Carter Lindberg notes, “unprecedented breathing space to Protestantism in England.”

Back in 1530, Henry had William Tyndale’s English translations of the Bible burned. But now, only five years later and at the behest of our boy Cranmer and his colleague-in-reform Cromwell, Henry encouraged English Bibles (based on Tyndale’s translations) to be placed in every church. Henry also dissolved the monasteries and confiscated their land. “What for Cranmer and Cromwell was a pious fraud was for Henry a lucrative source of revenue.”

|

| Hans Eworth [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons |

Henry never quite liked the Bishop’s Book and as alliances with the Germans became less crucial, and negotiations broke down, he sought to impose religious unity (or at least uniformity) along more conservative lines. At this point, at the end of the 1530s, Henry’s religious policy was being influenced more by conservatives like Stephen Gardiner and Thomas Howard, the Duke of Norfolk, than it was by Cranmer — though Cranmer retained his position as archbishop.

This led, in 1539, to the adoption of the Six Articles — which reaffirmed traditional doctrine with respect to clerical celibacy, confession, and most importantly, transubstantiation. It became known as the “whip with ten strings.” These were followed up, in 1534, by the King’s Book (corresponding to the Bishop’s Book), which assigned human beings a level of explicit cooperation with God in attaining justification. There were also restrictions placed on who was allowed to read the Bible in English.

There was quite a bit of heretic hunting in this more conservative period, of both alleged papists and Lutherans. Cromwell met his end during this time, accused of treason and heresy. Another name worth highlighting is that of Anne Askew — a Protestant martyr who was tortured on the rack and then burned at the stake. The strength of her conviction and her courage even in the face of death sets a remarkable example. That being said, her way was not Cranmer’s; and his way had something to commend it as well.

Much in this period must have horrified Cranmer. But he did not have a winning hand, and he knew it. It was time to fold ‘em, to stay alive and bide his time for another deal.

Cranmer was keeping his head down. It would be wrong, however, to suppose that he was out of the game entirely. He was working on a book of homilies. Also, in 1544 and at Henry’s request, he composed a litany in English that would later become the first installment of the Book of Common Prayer — his life’s most influential work.

---------------------------

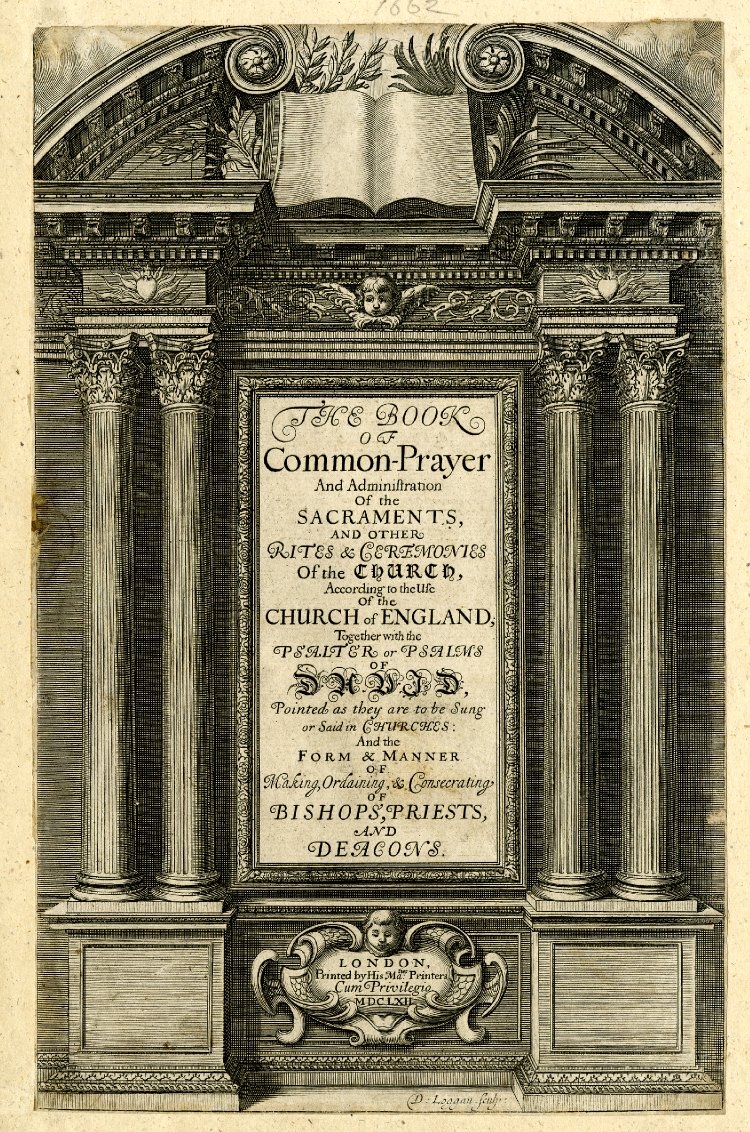

|

| By Church of England [Public domain], via Wikimedia Commons |

who had been taught by Protestants and who now had a series of Protestant regents ruling in his place.

Cranmer decided it was time to go all in.

His Book of Homilies countered the King’s Book with a clear and explicit affirmation of the doctrine of justification by grace alone. Through the first and second editions of Cranmer’s Book of Common Prayer (in 1549 and 1552 respectively), the English people were introduced to a Reformed understanding of the Eucharist that flatly denied transubstantiation and essential presence in favor of a modified form of Zwinglian memorialism that emphasized a “spiritual reception of Christ in the heart of the believer.” This understanding most closely resembled that of Heinrich Bullinger, Zwingli’s successor in Zürich. In the bread and the wine, believers remembered the once-for-all sacrifice of Christ on the cross and, in doing so, received Christ not bodily but spiritually. Church architecture was quickly changed to reflect the new reformed understanding, with stone alters being replaced by wooden tables (the former indicating a place of sacrifice while the latter a memorial meal).

In 1553, Cranmer’s new Forty-Two Articles of Religion were given royal assent. They outlined some important points of doctrine for the young reformed Church of England, and would later become the basis for the paired down Thirty-Nine Articles under Elizabeth I. His Book of Common Prayer, however — as much a genius compilation of biblical, ancient, and medieval liturgical sources as it was original poetic composition — was Cranmer’s most influential achievement by far.

Alan Jacobs notes:

the Book of Common Prayer . . . would transform the religious lives of countless English men, women, and children . . . [it] would mark the lives of millions as they moved through the stages of life from birth and baptism through marriage and on to illness and death and burial . . . [it] would accompany the British Empire as it expanded throughout the world . . . [and] versions of it are used today in Christian churches all over the world, as far from England as South Africa, Singapore, and New Zealand.

The core of a Protestant Church of England was therefore established during the reign of Edward VI, with Cranmer leading the charge. Unfortunately for him, Edward did not reign long. Having always been of precarious health, Edward died in 1553. Concerned that all their progress would be lost if Mary Tudor (a firmly committed Catholic) came to the throne, Cranmer joined a conspiracy to deny Mary the succession on the basis of her being “illegitimate” as the offspring of Henry’s “illegitimate” marriage to Catherine. Their plan was to pass the throne instead to Henry’s Protestant grandniece, the young Jane Grey.

For all his calculation and political savvy, here Cranmer overplayed his hand. He had gone all in on a king who, though favorable to Cranmer’s reform program, was not long for this world. The conspiracy was a failure; Mary Tudor took the throne, while Grey and the conspirators were sentenced to death.

---------------------------

The gambler in Kenny Roger’s song meets an almost idyllic end; right there on the train, he crushes out his cigarette and fades off to sleep. Cranmer was not so lucky.

He was imprisoned from 1553 until his death in 1556, and tried for heresy and treason. He was among the nearly three hundred Protestants that Queen Mary burned at the stake in her five short years in power. Before his own execution, Cranmer was made to watch his Protestant friends and colleagues burn. Lacking the kind of courage that was seen in the likes of Anne Askew, he signed a number of official recantations, allegedly reconciling himself to Catholicism. When it finally came time for his own execution though, Cranmer publically affirmed his Protestant convictions, recanting his former recantations, and dramatically holding out the hand with which he had signed the recantations over the flames to be consumed first.

---------------------------

Reformation in England, in the 16th century, was a high-stakes gamble. Cranmer was the man for the job because he knew how to play the game. He did what he needed to do to stay alive, and to make what advances he could. As a result, he had a monumental impact on the direction of the Christian faith in England and, by extension, on the faith experience of millions of Christians around the globe for centuries to come.

Chapman, Mark. Anglican Theology. New York, NY: T&T Clark, 2012.

Jacobs, Alan. The Book of Common Prayer: A Biography. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2013.

Lindberg, Carter. The European Reformations, 2nd Edition. Malden, MA: Wiley-Blackwell, 2010.

#Refo500atDET introduction and schedule available here.

==================================

Follow @WTravisMcMaken

Subscribe to Die Evangelischen Theologen

Comments