Americanity: or, Religious Studies with St. Hereticus (critical edition)

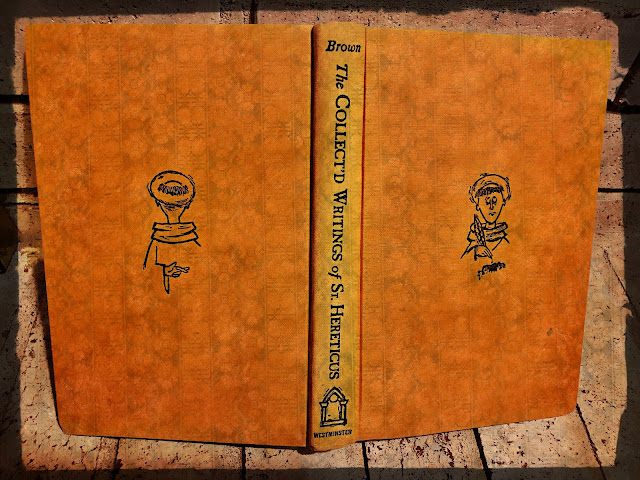

Robert McAfee Brown (ed.?), The Collected Writings of St. Hereticus (Philadelphia, PA: Westminster Press, 1964).

We harken once again to the words of The Saint. They were written a little more than half a century ago now, but so much of it continues to ring true – with the appropriate updates born in mind (where is the “prophetic school” to carry on the work of St. Hereticus when you really need it…) – even today that I could not, gentle reader, bear the thought of keeping it from you.

The Saint addresses a number of other leading world religions as well: for instance, Naturism, Lingoism, and Churchianity also attract his attention. But let us leave those worthy studies to the side for the present (although I encourage you to explore them yourself). I would call your attention to the religion that The Saint treats first, which I take to indicate precedence. You will find the following on p. 55–57 of the work cited above. As usual, bold is mine and italics are in the original.

Americanity

Although this is a religion of fairly recent origins as world religions go (it is less than two hundred years old as I count time), it has in recent years become, so its adherents would claim, the most important. It cannot with total accuracy be called a world religion, since there are still a great many people in such colonies as Europe, Asia, Africa, the Far East, the Near East, and the Arctic and Antarctic regions who have not yet been converted by its missionaries, though in the last named region there have been some indications recently of a shift in sentiment among the Penguins.*

Even in the Patristic Period, e.g., of the early church fathers, or as they are called in this case, the “founding fathers,” there were hints as to the direction in which the final credal formulations of this religion would crystallize. But it was a sentiment from the high Middle Ages that, clearly capturing the sense of total commitment demanded by any true religion, best epitomized the faith of the true adherents. This sentiment went (and still goes), “My country, right or wrong; may she always be right, but right or wrong, my country.” This absolute devotion to the claims of the deity has become more rather than less important in the later development of the religion.

Another creed of Americanity, which its apostles preach by their actions, and which is hence called the “apostles’ creed,” begins something like this: “I believe in America the nation almighty, creator of heaven on earth.” Variant readings make it impossible to quote the creed in its entirety, but it is significant that in no surviving rescension is there any reference to crucifixion, death, or burial. This is one religion that has a rising, but never a dying, savior-god.

Americanity has its own eschatology, or doctrine of the last things. When an adherent of the faith is asked about the meaning of history, where history is going, and in what he places his ultimate trust and hope, the answer is giving by the phrase, “the American century.”**… Coupled with this eschatology is a highly developed doctrine of the church, or the means of salvation. This doctrine is expressed in the classic words extra Americam nulla salus (outside America there is no salvation). The meaning of this doctrine is quite clear to adherents of the faith, and they hold it as a literal truth. No poor benighted European Continentals, or British socialists, or Indian neutralists, have a chance of entering the Kingdom of Man until they have been completely converted to Americanity. And those so-called Americans who want to participate in interfaith conferences with other nations, carrying on united negotiations (sometimes called “u.n.” for short) are clearly dangerous.

How is this faith passed on from generation to generation? This is done in highly orthodox fashion by a doctrine of apostolic succession, in which purity of belief, however, is guaranteed not by a laying on of hands but by transmission through the right wing. This perhaps accounts for the fact that nonbelievers sometimes refer to the stance of this faith as “ostrichlike,” a phrase that evokes particular horror on the part of the faithful, and prompts them to reply that their attackers are so angry that they are “seeing red.”

The doctrines of the faith are many and varied, but they have usually grown up out of a specific Sitz im Leben. Thus, for example, at one time in the history of the faith there was a doctrine known as the Monroe Doctrine. Recently, this has been modified by renaming it the Marilyn Monroe Doctrine, after a now deceased goddess, and involves sending photographs of the one from whom the doctrine derives its name to every portion of the mission field, where the apostles of Americanity are stationed in their ecclesiastical barracks. This has the twofold advantage of reminding the apostles what it is they are defending (every one of them being a defensor fidei), and also of pointing out to the adherents of other faiths the superior advantages of the culture produced by the religion of Americanity.

Wherein lies the great appeal of this religion? Most significantly perhaps in (1) the assurance with which it can claim to be the final hope of mankind; (2) the exclusiveness with which it can assert in the name of its deity, “Thou shalt have no other gods before me,” which in a briefly and more up-to-date translation goes, “America First”; (3) the wisdom of its benevolence program and almsgiving, which demands only that the recipients subscribe 100 percent to the creed of Americanity; and (4) the dedication of its priest-group, all of whom are prepared that heaven and earth should quite literally pass away before one jot or tittle of their creed be modified.***, ****

Notes:

(*) In his comment about the extent of Americanity, The Saint clearly has in mind only those who make conscious professions of faith. Even with that proviso, however, we must count this particular religion as having grown considerably since the time of his study. Additionally, the extent of what we might call “anonymous Americanity” has also made remarkable gains thanks to the missionary activity of global capital backed by Americanity’s military power. On this latter point, see The Saint’s comment toward the end of this study concerning “the apostles of Americanity…in their ecclesiastical barracks.”

(**) This “realizing eschatology” (Charry) became even more pronounced in Americanity at the end of the second millennium, when some proponents even declared “the end of history.” While many scholars of Americanity have submitted this declaration to devastating criticism (see Badiou), Americanity’s apologists – especially those featured on Americanity’s propaganda media network named after a fairly small member of the Canidae family – nonetheless continue upholding it.

(***) We ought to interpret this passage with reference to the nuclear arms race underway during the time when The Saint conducted this ground-breaking study. While nuclear armament remains an existential threat to humanity, we must interpret The Saint’s remark here in an expansive sense to include more recent crises such as global warming and other environmental crises.

(****) A number of points require making in conclusion:

- It is highly regrettable that The Saint did not extend his study to include the fertile sub-field of Americanity’s religious symbolism. One wonders, for instance, what he would make of such symbols as the lowercase “f” on the blue field, or of the arches of gold that so closely resemble an “m,” etc.

- Likewise with the sub-field of Americanity ritual studies, which might encompass events such as “Black Friday” and the other sale holidays (“holy-days”), “July 4th,” Superbowl Sunday,” etc.

- Comparative religious scholars will note that The Saint implicitly draws parallels to another religious tradition – namely, Christianity – in his discussion of Americanity. These parallels are extensive enough that they must have been intentional, and we are therefore justified in drawing the conclusion that The Saint recognized, even if only implicitly, the syncretistic character of Americanity. That syncretism has only increased, and expanded to incorporate innumerable other religions traditions, in the intervening years.

- For further reading on a similar subject from one of The Saint’s contemporaries, see: Writing Theology in America Requires Prolegomena - Paul M. van Buren’s “Austin Dogmatics”, Covenant vs. Cultural Religion - Paul M. van Buren’s “Austin Dogmatics”.

==================================

Follow @WTravisMcMaken

Subscribe to Die Evangelischen Theologen

Comments