Pagans in Heaven? Zwingli on "Anonymous Christianity"

Prominent theologians in recent decades have entertained some form of soteriological inclusivism. Briefly put, this notion means that God leaves open a path to eternal salvation for individuals who never profess explicit faith in Jesus Christ during their lifetimes. Might there be some sort of "back door" to heavenly bliss? At issue, for many, is fairness: Surely a loving God would make provision for hapless souls who never consciously confront the offer of salvation in Jesus, either through ignorance or just by being born at the wrong place or time.

The Jesuit theologian Karl Rahner proposed a form of “anonymous Christianity” that (some have thought) helps address this concern. Within the context of his transcendental Thomist framework, Rahner suggests individuals, somehow, might be able to muster an act of unconscious, existential freedom to accept the offer of divine grace. A more popular slant on this idea occurs in C.S. Lewis’ fantasy novel The Last Battle, wherein the officer Emeth gets a free ticket into Aslan’s country because of his noble intentions: All his life, the Calormene officer unwittingly served the evil deity Tash, but Aslan (one imagines Liam Neeson's soothing voice here) graciously accepts Emeth's well-intended piety as good enough to save him.

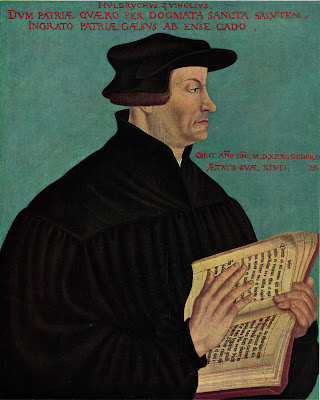

Perhaps neither Lewis nor Rahner realized that a provocative, often polemical Swiss Protestant Reformer had flirted with a form of proto-inclusivism four centuries earlier. Huldrych Zwingli, the early-16th erstwhile Catholic priest who led the newly established Protestant church in Zurich, proposed his own “anonymous Christianity” theory. Unlike the Rahnerian and Lewisian notions, though, which rely upon human free will, the Swiss Reformer built his theory on an entirely different basis -- an account of divine election as encompassing, gratuitous, and inscrutable. He argued that the wisdom of pre-Christian luminaries of classical antiquity may be a sign that God's providence was secretly at work among them, and that the faithful might be surprised to share the heavenly banquet with ancient Greek philosophers, military heroes, and wise rulers.

The Theology of Huldrych Zwingli, By W.P. Stephens (Clarendon Press, 1988).

As W.P. Stephens notes, Zwingli’s image of pagan luminaries covorting with the faithful in the heavenly realms drove Martin Luther to distraction: Wouldn’t this notion, the German Reformer charged, threaten to drive a wedge between salvation and the work of Christ? Put another way, is Zwingli's account of election too abstractly theocentric at the expense of the Gospel story of Christ's saving deeds?

What factors might account for this oddly irenic note in this iconoclastic Zuricher’s theology? To be sure, Zwingli drank more deeply and appreciatively from the wells of Renaissance humanism, with its characteristically warm view of classical antiquity, than did his counterpart in Wittenberg. As Stephens remarks, Zwingli was very moved by a poem by Erasmus extolling Christ as sole mediator of salvation (Luther, late in life, would increasingly be moved by the Dutch humanist scholar in less felicitous ways).

But the more interesting issues -- for me, at least -- are distinctively theological. As Stephens shows, Zwingli’s corpus is governed by a strong emphasis on divine providence; God's sovereignty is total, if not always explicable. Such a theological concern, of course, is hardly lacking in Luther’s work, but the German Reformer tends to interpret salvation in a more thoroughgoingly Christocentric way than Zwingli; and that commitment, as it turns out, tends to shape one's theological method. Stephens writes:

Zwingli’s startling move on election -- if I’ve read this correctly -- leaves several tricky theological questions to sort out. According to such an account of absolute sovereignty, God can elect whomever God wishes, for whatever reason, or for no apparent reason at all. If this is true, how can anyone set a fixed boundary upon the divine mercy? Moreover, what is the role of Christ’s saving death in such a soteriology? And what is the significance, for Zwingli, of Christ's human nature as the point of contact that mediates salvation to the rest of us? On another front, has the Zurich reformer, so impressed by the human virtues of the ancients and even some moderns, corrupted his strict predestinarianism with a dash of semi-Pelagian works, or perhaps better, intentions righteousness? These questions go beyond what I can discuss here.

Zwingli does insist, Stephens writes, that God's election of the faithful occurs in Christ. Still, why would it be necessary for Jesus to die on the cross if his death could be supervened by divine election in this fashion? Zwingli, Stephens writes, affirmed the centrality of the cross. But how might one integrate a "front door" economy of salvation with a "back door" in which the eternal divine council seems to be doing the heavy work? Perhaps Zwingli's move illustrates potential doctrinal ramifications if a theocentric account of divine sovereignty governs a Christocentric soteriology rather than vice versa.

In introducing the treatise "An Exposition of the Faith" (1529), G.W. Bromiley pegs the issue succinctly:

Moreover, just what is the role of faith in salvation? What do we make of the explicit human response to God's grace in Christ? It would be interesting to examine how the Reformers themselves might have interpreted faith differently from each other. On the face of it, Zwingli's picture of Theseus, Hercules, and Socrates in heaven would seem, at least, to relativize the question of saving faith (Does he mean the Hercules of history or the Hercules of faith?).

It is crucial for Zwingli, Stephens notes, to understand faith as consequent upon God’s eternal election; faith is a sign, not the source, of salvation. To be sure, neither Luther nor Calvin would want to see faith as anything other than gift rather than a meritorious work. But the next step, presumably, they will not take with Zwingli. Faith is a sign of salvation, they might all agree; but Zwingli also insists, explicit faith's absence is not necessarily a sign of reprobation. Zwingli abhorred the idea that unbaptized infants and the nonbelievers of pre-Christian antiquity were beyond hope of salvation. These ideas first come to the fore in Zwingli’s 1526 work Original Sin, wherein he deploys his account of election to argue against the notion that baptism is necessary for salvation. As Stephens notes, election also would be weaponized in Zwingli’s struggle against the anabaptists.

A crucial clue, perhaps, is that Zwingli’s doctrine of election originally emerged as a subsidiary concern to his doctrine of providence, only to be tied more closely to soteriology in later writings. And this being the sort of website it is, I can't help but name drop another famous Swiss theologian: How might it look different if the doctrine of election were (re)framed Christologically root and branch, as Karl Barth (in)famously recast the doctrine in his Church Dogmatics?

==================================

Follow @jsjackson15

The Jesuit theologian Karl Rahner proposed a form of “anonymous Christianity” that (some have thought) helps address this concern. Within the context of his transcendental Thomist framework, Rahner suggests individuals, somehow, might be able to muster an act of unconscious, existential freedom to accept the offer of divine grace. A more popular slant on this idea occurs in C.S. Lewis’ fantasy novel The Last Battle, wherein the officer Emeth gets a free ticket into Aslan’s country because of his noble intentions: All his life, the Calormene officer unwittingly served the evil deity Tash, but Aslan (one imagines Liam Neeson's soothing voice here) graciously accepts Emeth's well-intended piety as good enough to save him.

Perhaps neither Lewis nor Rahner realized that a provocative, often polemical Swiss Protestant Reformer had flirted with a form of proto-inclusivism four centuries earlier. Huldrych Zwingli, the early-16th erstwhile Catholic priest who led the newly established Protestant church in Zurich, proposed his own “anonymous Christianity” theory. Unlike the Rahnerian and Lewisian notions, though, which rely upon human free will, the Swiss Reformer built his theory on an entirely different basis -- an account of divine election as encompassing, gratuitous, and inscrutable. He argued that the wisdom of pre-Christian luminaries of classical antiquity may be a sign that God's providence was secretly at work among them, and that the faithful might be surprised to share the heavenly banquet with ancient Greek philosophers, military heroes, and wise rulers.

The Theology of Huldrych Zwingli, By W.P. Stephens (Clarendon Press, 1988).

As W.P. Stephens notes, Zwingli’s image of pagan luminaries covorting with the faithful in the heavenly realms drove Martin Luther to distraction: Wouldn’t this notion, the German Reformer charged, threaten to drive a wedge between salvation and the work of Christ? Put another way, is Zwingli's account of election too abstractly theocentric at the expense of the Gospel story of Christ's saving deeds?

What factors might account for this oddly irenic note in this iconoclastic Zuricher’s theology? To be sure, Zwingli drank more deeply and appreciatively from the wells of Renaissance humanism, with its characteristically warm view of classical antiquity, than did his counterpart in Wittenberg. As Stephens remarks, Zwingli was very moved by a poem by Erasmus extolling Christ as sole mediator of salvation (Luther, late in life, would increasingly be moved by the Dutch humanist scholar in less felicitous ways).

But the more interesting issues -- for me, at least -- are distinctively theological. As Stephens shows, Zwingli’s corpus is governed by a strong emphasis on divine providence; God's sovereignty is total, if not always explicable. Such a theological concern, of course, is hardly lacking in Luther’s work, but the German Reformer tends to interpret salvation in a more thoroughgoingly Christocentric way than Zwingli; and that commitment, as it turns out, tends to shape one's theological method. Stephens writes:

[I]n spite of the indispensable, and in many ways central, place that Christ had for Zwingli, he was not the beginning, middle and end of Zwingli’s theology as he was for Luther’s. Moreover the Christ on whom Zwingli concentrated was Christ as God rather than as man (p. 54).

Zwingli’s startling move on election -- if I’ve read this correctly -- leaves several tricky theological questions to sort out. According to such an account of absolute sovereignty, God can elect whomever God wishes, for whatever reason, or for no apparent reason at all. If this is true, how can anyone set a fixed boundary upon the divine mercy? Moreover, what is the role of Christ’s saving death in such a soteriology? And what is the significance, for Zwingli, of Christ's human nature as the point of contact that mediates salvation to the rest of us? On another front, has the Zurich reformer, so impressed by the human virtues of the ancients and even some moderns, corrupted his strict predestinarianism with a dash of semi-Pelagian works, or perhaps better, intentions righteousness? These questions go beyond what I can discuss here.

Zwingli does insist, Stephens writes, that God's election of the faithful occurs in Christ. Still, why would it be necessary for Jesus to die on the cross if his death could be supervened by divine election in this fashion? Zwingli, Stephens writes, affirmed the centrality of the cross. But how might one integrate a "front door" economy of salvation with a "back door" in which the eternal divine council seems to be doing the heavy work? Perhaps Zwingli's move illustrates potential doctrinal ramifications if a theocentric account of divine sovereignty governs a Christocentric soteriology rather than vice versa.

In introducing the treatise "An Exposition of the Faith" (1529), G.W. Bromiley pegs the issue succinctly:

Zwingli could make the assertion [that pious heathen will be saved] because it was congruent with his whole conception of the divine sovereignty and the election of grace. The redemptive purpose and activity of God was not limited by the chronology and the geography of the incarnation and the atonement (Zwingli and Bullinger, Westminster John Knox, 1953, p. 242).

| IndianCaverns / Public domain from Wikimedia Commons |

It is crucial for Zwingli, Stephens notes, to understand faith as consequent upon God’s eternal election; faith is a sign, not the source, of salvation. To be sure, neither Luther nor Calvin would want to see faith as anything other than gift rather than a meritorious work. But the next step, presumably, they will not take with Zwingli. Faith is a sign of salvation, they might all agree; but Zwingli also insists, explicit faith's absence is not necessarily a sign of reprobation. Zwingli abhorred the idea that unbaptized infants and the nonbelievers of pre-Christian antiquity were beyond hope of salvation. These ideas first come to the fore in Zwingli’s 1526 work Original Sin, wherein he deploys his account of election to argue against the notion that baptism is necessary for salvation. As Stephens notes, election also would be weaponized in Zwingli’s struggle against the anabaptists.

A crucial clue, perhaps, is that Zwingli’s doctrine of election originally emerged as a subsidiary concern to his doctrine of providence, only to be tied more closely to soteriology in later writings. And this being the sort of website it is, I can't help but name drop another famous Swiss theologian: How might it look different if the doctrine of election were (re)framed Christologically root and branch, as Karl Barth (in)famously recast the doctrine in his Church Dogmatics?

==================================

Follow @jsjackson15

Comments