What Am I Reading? No Other Name by John Sanders

In my post last week, I offered a somewhat whimsical entree to John E. Sanders' impressive book on the scope of salvation. I then received a tip that an anonymous interlocutor thinks this book deserves some closer exposition, so I've been reading it carefully during this past week. I have not been disappointed. Sanders did his research and produced a truly fine, and eminently useful, work in historical and constructive theology.

No Other Name: An Investigation into the Destiny of the Unevangelized, by John E. Sanders (Eeerdmans, 1992).

The animating question in Sanders' book is this: What, as Christians, can we say about the fate of those who never hear the Gospel of Jesus Christ explicitly proclaimed, or who through some incapacity are simply unable to receive it?

Sanders writes from a conservative evangelical perspective, and he masterly refutes the caricature that what he calls restrictivist soteriology is the only serious option on the table in the history of conservative Protestant thought. Restrictivists, he writes, believe that "the only legitimate answer to the question of the destiny of the unevangelized is that there is no hope whatsoever for salvation apart from their hearing the message about the person and work of Christ and exercising faith in Christ before they die" (p. 37). Taken to its logical extreme, this view entails that the vast majority of humankind throughout the ages is lost -- including members of other religious traditions and even infants who die before they can make a decision for faith. While a number of key thinkers -- particularly within Reformed orthodoxy and old-school Roman Catholicism -- have toed the line on this position, Sanders shows that there have always been dissenters, and, especially since the dawn of modernity, an increasing number of believers (evangelicals included) have found themselves unable to stomach restrictivism and its concomitant claims about the nature of God and human destiny.

He states the issue poignantly in his preface:

The dilemma stems from holding two claims that, on the face of it, might seem incongruous: On the one hand, New Testament passages such as 1 Tim. 2:3-4 seem to claim that God desires the salvation of everyone. On the other hand, passages such as Acts 4:12 seem to claim that "the particularity and finality of salvation" reside in Christ alone, and that personal salvation entails explicit faith in him (p. 25). Obviously, if either of these claims is qualified, weakened, or rejected, the issue will need to be re-framed (for example, in accounts of double predestination and limited atonement).

Of course, one major alternative that eschews this dilemma entirely is universalist soteriology -- the claim that, in the end, all human beings will be saved, whether through divine fiat or through the effects of God's persuasive love working in and through human free will. In early chapters of the book, Sanders offers fair-minded and clear summaries and evaluations of both restrictivist and universalist positions -- exploring both the biblical foundations and theological implications of these two schools of thought and offering helpful annotated bibliographies for further research.

In the final chapters, Sanders explores various versions of a "wider hope" soteriology -- the approach that he finds the most promising. He shows that this school of thought ramifies into a variety of approaches, including theologians who argue that everyone eventually will encounter the gospel, whether in this life or at the moment of death; or that everyone who missed out in this life will be evangelized in the afterlife; or that everyone who seeks God or has implicit faith will ultimately be saved, whether or not they ever learn anything about Jesus whatsoever. This last option, known as inclusivism, can boast a very wide -- and growing -- currency among post-Vatican II Roman Catholics, mainline-liberal Protestants, and (increasingly) conservative evangelicals.

I envision certain kinds of readers who might not find a study of this compelling, or perhaps even interesting: An increasing number of revisionist, radical, and post-Christian theologians view any notion of post-mortem salvation for individuals as inherently problematic. Some might be liberationists focused on retrieving and reinterpreting Christian soteriology to focus on concrete socio-political and spiritual transformation in this life, in this world. They might be existentialists who would demythologize Christian soteriology to emphasize the decision for an authentic existence in the here and now. Or they might be process thinkers who believe the lives of all people, after the light of personal consciousness has been extinguished, are redeemed through incorporation into the broader cosmic whole that is the divine life and memory. And then there are the atheists and agnostics....

I do believe, though, that there is something useful for most everyone in a book like this, so, gentle readers, please stay tuned for more to come.

==================================

Follow @jsjackson15

No Other Name: An Investigation into the Destiny of the Unevangelized, by John E. Sanders (Eeerdmans, 1992).

The animating question in Sanders' book is this: What, as Christians, can we say about the fate of those who never hear the Gospel of Jesus Christ explicitly proclaimed, or who through some incapacity are simply unable to receive it?

|

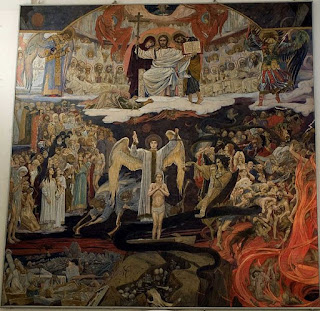

| The Last Judgment, by Viktor Vasnetsov (1904) Photo by Scatestle (Via Wikimedia Commons, PD-1994) |

Sanders writes from a conservative evangelical perspective, and he masterly refutes the caricature that what he calls restrictivist soteriology is the only serious option on the table in the history of conservative Protestant thought. Restrictivists, he writes, believe that "the only legitimate answer to the question of the destiny of the unevangelized is that there is no hope whatsoever for salvation apart from their hearing the message about the person and work of Christ and exercising faith in Christ before they die" (p. 37). Taken to its logical extreme, this view entails that the vast majority of humankind throughout the ages is lost -- including members of other religious traditions and even infants who die before they can make a decision for faith. While a number of key thinkers -- particularly within Reformed orthodoxy and old-school Roman Catholicism -- have toed the line on this position, Sanders shows that there have always been dissenters, and, especially since the dawn of modernity, an increasing number of believers (evangelicals included) have found themselves unable to stomach restrictivism and its concomitant claims about the nature of God and human destiny.

He states the issue poignantly in his preface:

How can we believe that God is just and loving if he fails to provide billions of people (including infants who die) with any opportunity to participate in salvation through Jesus Christ? Why did God create so many people if he knew that the vast majority of them would have no chance of ultimate salvation? On the other hand, if the unevangelized do have an opportunity for salvation, how is it made available to them (p. xvii)?

The dilemma stems from holding two claims that, on the face of it, might seem incongruous: On the one hand, New Testament passages such as 1 Tim. 2:3-4 seem to claim that God desires the salvation of everyone. On the other hand, passages such as Acts 4:12 seem to claim that "the particularity and finality of salvation" reside in Christ alone, and that personal salvation entails explicit faith in him (p. 25). Obviously, if either of these claims is qualified, weakened, or rejected, the issue will need to be re-framed (for example, in accounts of double predestination and limited atonement).

Of course, one major alternative that eschews this dilemma entirely is universalist soteriology -- the claim that, in the end, all human beings will be saved, whether through divine fiat or through the effects of God's persuasive love working in and through human free will. In early chapters of the book, Sanders offers fair-minded and clear summaries and evaluations of both restrictivist and universalist positions -- exploring both the biblical foundations and theological implications of these two schools of thought and offering helpful annotated bibliographies for further research.

In the final chapters, Sanders explores various versions of a "wider hope" soteriology -- the approach that he finds the most promising. He shows that this school of thought ramifies into a variety of approaches, including theologians who argue that everyone eventually will encounter the gospel, whether in this life or at the moment of death; or that everyone who missed out in this life will be evangelized in the afterlife; or that everyone who seeks God or has implicit faith will ultimately be saved, whether or not they ever learn anything about Jesus whatsoever. This last option, known as inclusivism, can boast a very wide -- and growing -- currency among post-Vatican II Roman Catholics, mainline-liberal Protestants, and (increasingly) conservative evangelicals.

I envision certain kinds of readers who might not find a study of this compelling, or perhaps even interesting: An increasing number of revisionist, radical, and post-Christian theologians view any notion of post-mortem salvation for individuals as inherently problematic. Some might be liberationists focused on retrieving and reinterpreting Christian soteriology to focus on concrete socio-political and spiritual transformation in this life, in this world. They might be existentialists who would demythologize Christian soteriology to emphasize the decision for an authentic existence in the here and now. Or they might be process thinkers who believe the lives of all people, after the light of personal consciousness has been extinguished, are redeemed through incorporation into the broader cosmic whole that is the divine life and memory. And then there are the atheists and agnostics....

I do believe, though, that there is something useful for most everyone in a book like this, so, gentle readers, please stay tuned for more to come.

==================================

Follow @jsjackson15

Comments

My views are pretty simple ( and at 72yrs,that's really ok= but there are always questions that can be looked into a bit deeper)So, here I am opening up some new areas for me to think about. I hope God will allow me this little meander away from my normal pathways,and give me His wisdom into whether this is an area of importance for me or just a informational read.

Regards,

Marje Erasmus.